An unlikely political friendship: Harold Macmillan & Tam Dalyell

A question about whether 'laity' should be able to understand Parliamentary bills revealed how an ailing prime minister treated a novice MP.

Image: Harold Macmillan. Source: Wikipedia.

An unlikely political friendship: Harold Macmillan & Tam Dalyell

by Lee David Evans

‘Dalyell, come here!’

The young Tam Dalyell, among the most junior of MPs, turned around to see who wanted his attention. He was amazed to see it was the prime minister, Harold Macmillan.

The year was 1963. Dalyell had entered parliament just a year earlier when he won the West Lothian by-election. The contest had been a bleak one for Macmillan, with the Unionist candidate dropping 28 percentage points, slumping to third place and losing their deposit. (The threshold for keeping a deposit was 12.5 percent from the end of the First World War until 1985 so it wasn’t quite as humiliating as the 5 percent threshold today, but still bruising). It was one of several by-election blows for the Tories in 1962, including the more famous loss of Orpington to the Liberals - a formerly safe seat which neighboured Macmillan’s own.

Macmillan’s woes continued into the following year. In January, French President Charles de Gaulle ended British hopes of joining the European Economic Community with his three letter rebuke: “non”. Within weeks, rumours began swirling about the Secretary of State for War, John Profumo, and his relations with a showgirl. The ensuing scandal would be a permanent stain on this period of Macmillan’s leadership. Things were not looking good for ‘Supermac’.

Yet even as Macmillan began to look as if he would succumb to the pressures of politics at the top, he wanted to do a service for a relatively new MP. A week before the prime minister beckoned the junior MP, Dalyell, a fellow old Etonian, had asked Macmillan a question in the Commons, specifically: will he ‘ensure that legislation presented to this House is not drafted in obscure language?’

Macmillan replied briefly by citing the need for precision about complex and technical issues. But Dalyell, a little unsatisfied with the response, pushed back and asked, ‘is it not also important that we laity should understand legislation?’

Macmillan gave an answer which was as typically him as any you could find:

I know that this is a difficult problem. I would remind the House of the very wise words of Sir James Stephen, one of our greatest authorities, who pointed out that since legislation is often the subject of litigation it is absolutely necessary not only that it should appear to be simple to those who read it in good faith, but actually precise. That is a very difficult art. Many things are simple. Let us take the sentence: “When John met his uncle in the street he took off his hat.” That is a clear sentence, but it is capable of at least six different meanings. The point about legislation is that the courts have to interpret it in litigation based upon it, and it is therefore essential that it should be not so much simple as precise.

Many prime ministers might have thought that the end of the matter - a question asked, and answered, so time to move on. But a week later Dalyell was walking through a corridor in Parliament when Macmillan shouted to him. ‘I was not unsympathetic towards your question,’ the prime minister said, ‘so I shall arrange for the chief parliamentary draftsman to show you exactly why I gave the answer that I did.’ Macmillan then did exactly that. Sir Noel Hutton met with Dalyell the following day. Dalyell recalled:

… He was an extremely distinguished QC and he came armed with endless volumes. I have not been taken apart like that since I was a first-year student - in the nicest way.

Dalyell saw it as a testament to the sort of prime minister, MP and man that Macmillan was:

… that the Prime Minister should go to such trouble for a young opponent to whom he owed absolutely nothing and who had been an embarrassment to him in the West Lothian by-election… was an act of generosity that is not forgotten.

Their political friendship, such as it was, was brief. Macmillan resigned later that year. The direct cause of his departure from office was ill health, but had his political fortunes been better he may well have sought to withstand the challenges of the surgeon’s knife in office (contrary to many reports, he did not think he was dying when he made the decision to resign). Macmillan left Parliament the following year and waited almost twenty years before joining the House of Lords as Earl of Stockton. He died in 1986.

As Macmillan departed the Commons, Dalyell’s long parliamentary career was only just beginning. He remained in the Commons until 2005, spending his last term as Father of the House (a role he inherited from Sir Edward Heath). Throughout his parliamentary career, he was often remarkable for his eccentric views: opposing Britain’s efforts to recapture the Falklands War, which put him in a minority of all MPs, and opposing Scottish devolution, which made him a minority in his own party - even if, on that occasion, he found more support on the other side of politics. He never joined the House of Lords but did enjoy the status of a baronet. Sir Tam Dalyell died in 2017.

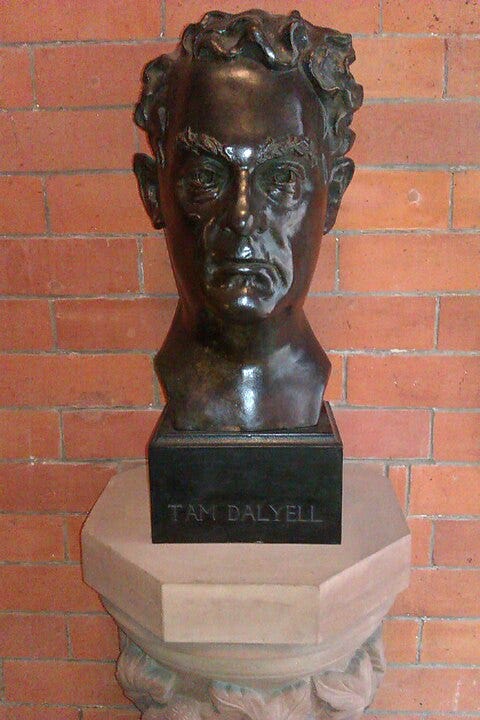

Image: A bust of Tam Dalyell. Source: Wikipedia.

Like this post? Click the ‘heart’ below to help other people find it on Substack. Please also feel free to share this post with anyone you think may be interested.