'Battling Bessie' - Snippets from the life of a Scouse icon

Recalling the life and career of one of the most characterful politicians of the last century: Bessie Braddock, MP for Liverpool Exchange (1945-70).

'Battling Bessie': Snippets from the life of a Scouse icon

by Lee David Evans

In spite of the controversy of recent years, I still believe statues are a force for good. They can celebrate great people as well as all they achieved; boost local pride by memorialising the noteworthy men and women born and raised in every part of the United Kingdom; and, sometimes, they can help prevent remarkable people from being forgotten by those who, whether they know it or not, stand upon their shoulders.

For me, growing up around Liverpool, I saw statues which did all those things. They included a statue of Bessie Braddock, perhaps the most charismatic Liverpool politician of the twentieth century, which has stood in bronze opposite fellow Scouse icon Ken Dodd at Lime Street station since 2009.

People in Merseyside have a habit of telling you politics runs in their family - socialist politics, at that. It certainly did for Braddock. Her mother, Mary Bamber, was an early trade union organiser. To avoid any risk that her daughter wouldn’t be a chip off the old block, the young Elizabeth ‘Bessie’ Bamber was sent to Socialist Sunday School and learned her gospel alongside the tenets of socialism. It’s said that the day Bessie left home, at 15, for her first day working at the Walton Road Co-op, her mother called after her, ‘don't come back until you have joined the union!’

Her political childhood was a sign of things to come. Her entire life would be steeped in politics, first as a member of the Communist Party (her mother was a founding member) and then, from 1924 onwards, in the Liverpool Labour Party. Alongside her husband Jack, whom she married in 1922, Braddock established herself as a powerful force in Merseyside politics. Like so many politicos throughout the years, they began by getting elected to the Council. Jack earned his place representing the Everton ward on Liverpool City Council in 1929 and Bessie followed a year later representing St. Anne’s. She would serve as a Councillor until 1961.

From Council Chamber to House of Commons

By the mid 1930s Bessie had decided to redirect some of her energy from the Council chamber to the House of Commons. She was selected in 1936 to contest the Liverpool Exchange constituency, which had been won by a Tory the previous year, but the extension of the Parliament during the war denied her the chance to fight for a place on the green benches for another nine years. With victory in Europe secure, she got her chance in the 1945 election. A 9.2% swing gave her both the seat and the right to call herself the first Labour woman to sit for a Liverpool constituency. Her majority was a perilously small 665 votes, yet in a sign of her local appeal and the shifting tides of Liverpool politics, her margin of victory in Labour’s landslide year was the smallest of her career.

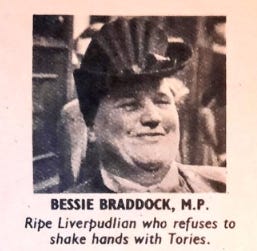

Braddock was described as a ‘ripe Liverpudlian’ and singled out for her hostility to Tories in the Picture Post's preview of the 1952 Labour conference held in Morecambe.

Braddock wasted no time in putting her fellow MPs on warning about her approach to politics, telling them in her maiden speech, ‘All my life I have been an agitator against the conditions… in which my class has been compelled to live and I shall continue to agitate with every means and power I have.’ Her actions would often rub people up the wrong way.

On one famous occasion in 1956, Braddock raised her concerns about the availability of air guns. ‘Many people in the country have lost their sight, or have been otherwise injured, as a result of their use,’ she said, demanding the government change the rules to limit their sale. Having sensed she was failing to make her case, and frustrated by the Deputy Speaker who raised procedural issues against her, Braddock took ‘three air-rifles, which she had seized from juveniles in Liverpool, [and fired] the unloaded rifles into the air’, before saying, ‘I will hand them now to the Home Secretary, so that he can see what children can buy’.

The Deputy Speaker was not best pleased. ‘The honourable lady is out of order in bringing those things into the Committee,’ he warned, before rebuking the Liverpool firebrand for walking across the floor of the Commons chamber in the course of her speech. The unmoved Braddock all but bit her thumb in the direction of the Speaker’s Chair, insisting, ‘No one takes any notice unless someone does something which is out of order,’ and added, ‘I know I was out of order... I did it deliberately!’

Exchanges like this were vintage Braddock. Shocking, confrontational, even outside of the rules. But underlying it all was a serious issue and a genuine concern for her constituents. When once asked about her approach to politics, she said, ‘Of course I'm aggressive - when there is something to be aggressive about.’ She even linked her confrontational politics to her sex, saying ‘Women are far more tenacious than men.’

From the left to battling the left

In her pre-Parliamentary years, it was possible to dismiss Braddock as a far-left extremist. After all, she had been a member of the Communist Party. Yet her experiences in politics brought a shift in perspective; by the time she was established on the green benches, Bessie would have been unrecognisable to her erstwhile communist friends. She had transitioned to the Labour Right.

As an MP, she regularly vied against the hero of the Labour Left, Nye Bevan. At the 1952 Labour conference, she lashed out against his ‘usual bad faith and bad language to the members of the party’. When a voice in the audience told her to ‘Go home!’ she turned on them, bellowing, ‘Those belonging to the Communist Party can go home!’ She went on, 'Aneurin Bevan at [a previous] Conference made this comment to me, and any delegate who was in the audience will remember it: "Let the dog see the rabbit". I am the rabbit now. Where is the dog?!'.

Her battles with the left inflicted bruises on her, including when her local party narrowly deselected her in 1952, only to have the legitimacy of the vote doubted and then dismissed by Labour’s National Executive Committee (of which Braddock was a member). It likely only stiffened her resolve. As a member of Labour’s main organising committee from 1947-69, she played a key role in candidate selection and helped keep out communist and Trotskyist infiltrators from the party. She was so proud of her work that she published the list of proscribed organisations for Labour members as an appendix to her memoirs.

Legacy

Despite being in Parliament for 25 years Braddock never made ministerial rank, having turned down a role in Harold Wilson’s government in 1964. Some say she refused his offer on the grounds of ill-health and old-age (she was 65). Others have suggested that she preferred the role of Chair of the Kitchen and Refreshment Rooms Select Committee, which made her the first woman to chair a Select Committee. She died in 1970, shortly after standing down as MP.

In spite of never joining the ranks of government ministers, she left her mark on Liverpool, on the Labour Party, and on Parliament. Throughout her life she recalled the scenes of her youth, including ‘the faces of the unemployed... their dull eyes and their thin, blue lips… [their] blank hopeless stares, day after day, week after week.’ She took these experiences into Parliament with her. Whilst her response to these issues may have changed as her politics evolved, her concern for the working-class of her home city never faltered.

With her demise politics lost not just a scrappy politician and a fighter par excellence, but a link with the noble past of Labour’s founding and the principles it inspired. In their obituary, the New York Times hailed her as ‘one of the last of a dwindling band of Labor members of Parliament whose socialism was fashioned in the days of soup kitchens and hunger marches’. That generation has now dwindled to nothing. Yet Braddock’s Lime Street statue, and the remarkable life it represents, is there to remind us.

P.S. What of the infamous clash between Braddock and Winston Churchill? Many Churchill anecdotes are untrue or unprovable, but there are good grounds to think she did once say to Britain’s wartime premier, ‘Winston, you are drunk,’ only for him to retort, ‘But tomorrow I shall be sober and you will still be ugly.’ The International Churchill Society has a brief blogpost on it from 2011, which you read here.

Liked this post? Click the ‘heart’ below to help other people find it on Substack.