Macmillan's 20 year wait to join the House of Lords.

Some digging in the National Archives sheds light on the twenty year gap between Harold Macmillan's resignation as prime minister and his ennoblement as Earl of Stockton.

Macmillan's 20 year wait to join the House of Lords

by Lee David Evans

On 18th October 1963, Harold Macmillan resigned as prime minister. It was an unusual resignation: hardly a soul outside of the tight circle around Macmillan knew, at the time of his resignation, who would take his place in Number 10; Macmillan himself was in hospital, recovering from a prostate operation; and for the first and only time in her reign, the Queen came to see her departing prime minister, rather than the other way around.

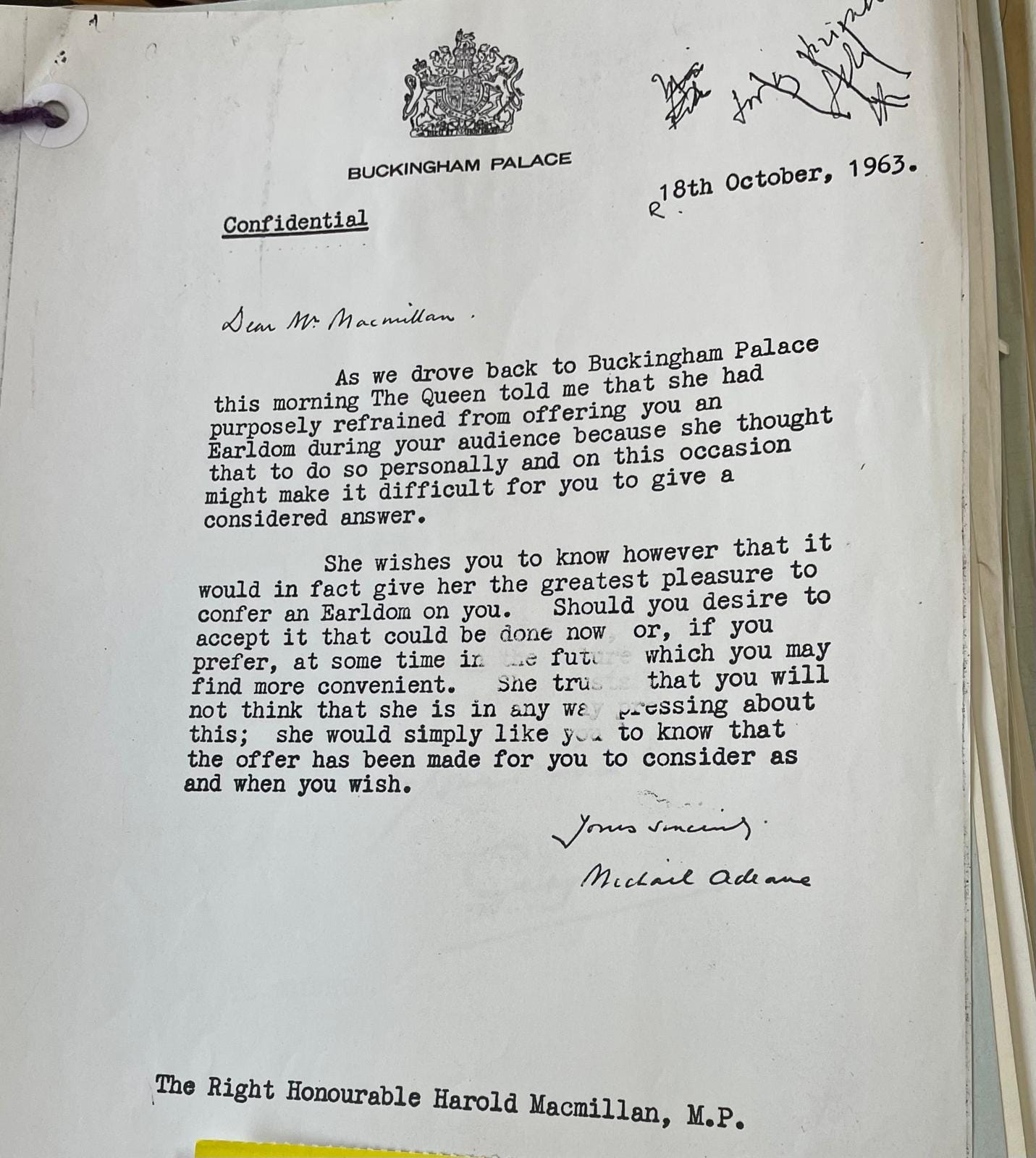

As is the custom for conversations between monarchs and their prime ministers, we know very little about what was said by Macmillan or the Queen. But whilst we cannot know exactly what was discussed, we know what wasn’t: the question of Macmillan’s future status as peer or commoner. In the National Archives there is a letter sent later that day from Sir Michael Adeane, the Queen’s Private Secretary, to Macmillan. Adeane wrote:

An Earldom was (but alas no longer is) the custom for a former premier. Macmillan’s immediate predecessor, Anthony Eden, became Earl of Avon. Attlee, Baldwin, Lloyd-George, Asquith, Balfour and others had all accepted Earldoms, too, with the exceptions usually a consequence of dying whilst still an MP or some particularity of the retiring prime minister.

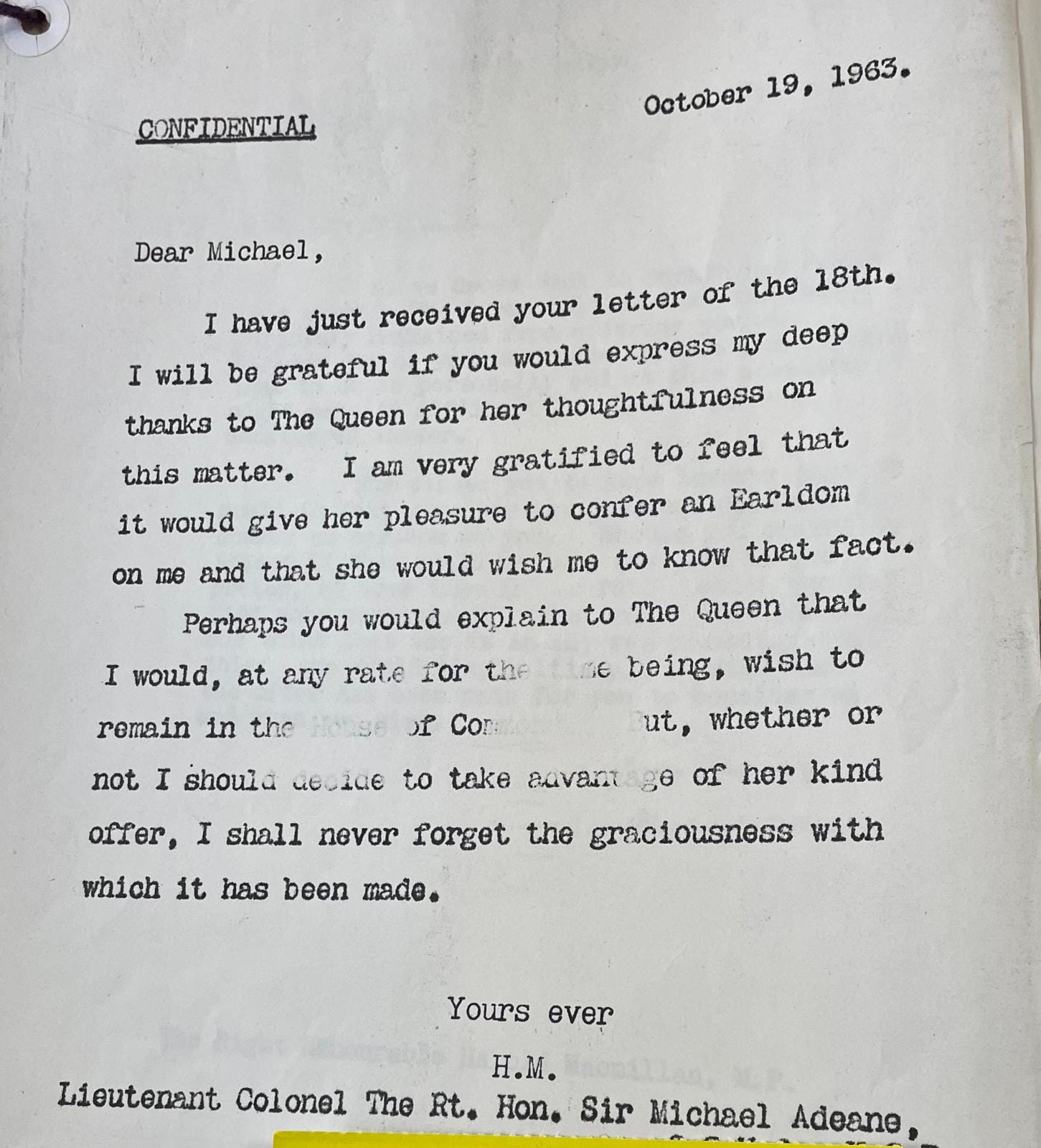

To Adeane’s generous note, Macmillan replied the very next day from his hospital bed:

‘The time being’, as Macmillan put it, would last two decades. Macmillan finally accepted the Queen’s offer on 10th February 1984, his ninetieth birthday. So why did he wait so long?

We can dismiss the reason Macmillan gave to the Queen, via Michael Adeane, when the offer was made, specifically that he wished ‘to remain in the House of Commons’. Macmillan stood down as MP for Bromley at the 1964 election, just one year later. He would only speak in the Commons three times after leaving Number 10: when Kennedy was assassinated, when the Denning report (into issues during his premiership, including the Profumo scandal) was published, and in praise of Churchill just before dissolution. It’s implausible that his attachment to the Commons kept him from swapping green leather for red when he surrendered his place in the Commons very shortly after standing down as prime minister.

Macmillan occasionally offered another explanation: modesty. ‘It was not in the family style,’ he once said, with reference to the humble Scottish crofter ancestry which Macmillan loved to emphasise. It’s true that he felt a certain shyness when it came to honours. In 1964 the Queen invited him to become a Knight of the Order of the Garter, the highest order of chivalry. He declined, apparently feeling it should only be awarded for service during a time of national crisis. Modesty was only a small part of Macmillan’s personality, however - after all, he gloried in the (originally sarcastic) name of ‘Supermac’ and always knew how to keep himself in the public eye and attract the attention of the chattering classes. It seems unlikely he would decline a peerage because of modesty alone.

More plausible is Macmillan’s concern for the political career of his son. With the resignation of Harold as prime minister, Maurice Macmillan, himself an MP, finally achieved ministerial office as Economic Secretary to the Treasury in Sir Alec Douglas-Home’s government. It was a moment of great pride for the elder Macmillan, who had resisted advancing his own son up the greasy pole. With Maurice’s career on the rise, a hereditary Macmillan peerage could have unsettled the hopes of the heir. Should the elder Macmillan die, would Maurice disclaim his father’s peerage? Or would he take it, but find a newly imposed glass ceiling on his ambitions? Avoiding this dilemma could have been a factor in Harold Macmillan’s mind.

Alistair Horne, Macmillan’s official biographer, suggests a further reason for postponing the peerage: to ‘keep open his own political options.’ Horne goes on: ‘At various times over the succeeding two decades [since his resignation, Macmillan] would drop hints… at a return - possibly at the head of a centrist coalition, a new national government, a new “Grand Design”.’ It’s all a bit fanciful - and never came close to happening - but it is just possible Macmillan thought a desperate nation would come knocking at his door and urge him to lead it. Should it have done so, he wanted to be available to lead from the Commons.

Whatever the reasons for the delay, by the time Macmillan became Earl of Stockton in 1984 all the causes for doubt had resolved themselves. His own age and infirmity now ruled out a comeback. His son’s health meant his career prospects were no longer a factor; Maurice would hold the courtesy title of Viscount Macmillan of Ovenden for just 30 days, dying 3 years before his father. If anything, familial reasons had shifted, as Macmillan’s grandson (the present Earl) apparently encouraged him to take up the title. What’s more, both the Queen and Mrs Thatcher had been encouraging Britain’s most prominent elder statesman to take the honour, too, according to Horne. If nothing else, as Macmillan celebrated his tenth decade on earth (and eighth decade in politics) perhaps he simply decided that the House of Lords would now be the best arena for him to make his rare, but powerful, political contributions.

You can watch two of Macmillan’s speeches in the Lords on Youtube:

Liked this post? Click the ‘heart’ below to help other people find it on Substack.

His performances in the Lords were spell-binding. Vintage Supermac.

I wonder if "not in the family style" may have had another meaning. Yes, his great-grandfather was a crofter, but his father-in-law was a Duke, and his relations with his wife and her family were famously difficult.