Parliamentary tributes to… Harold Wilson

In May 1995 Harold Wilson died. Parliament met - with Wilson's widow watching on - to offer its praise and tribute to one of the most remarkable politicians of the twentieth century.

Image: Gerald R. Ford Library

Parliamentary tributes to… Harold Wilson

by Lee David Evans

On 24th May 1995, almost two decades after he left Downing Street, Harold Wilson, Lord Wilson of Rievaulx, died. He was only the third person to serve as a Labour prime minister and unique among his socialist peers in having won four general elections (albeit three by the tightest of margins). He had been out of the public eye for a long time suffering from dementia, but his legacy loomed large in British politics and on the very day he died both the Commons and the Lords met to offer their tributes.

Conservative Prime Minister John Major led the mourning. His speech was largely biographical and somewhat pedestrian, but it included effusive praise:

I do not believe that it is too generous to describe Harold Wilson as one of the most brilliant men of his generation.

And ended with a very human description of his predecessor-but-two:

What was Harold Wilson really like? I have formed my judgement. He was a complex man, certainly, a clever man, a sensitive man, a man who could be bruised and hurt and who never wore the armadillo skin of the fictional politician. He was a man of many achievements and, perhaps above all, a very human man who served his country well and honourably and who has earned, by that, a secure place in its history. In the ledger of life, his credit balance is very high. It is a privilege for me, as one, nominally, of his political opponents, to pay him this tribute and I do so unreservedly.

Next up was Tony Blair, the man hoping to follow in Wilson’s footsteps and enter Number 10 wearing a red rosette. Blair used his remarks to highlight how he was of a different political era - ‘I was barely 11 years old when Harold Wilson became Prime Minister’ - before focusing on the ways Wilson had dominated British politics in his time:

[He] was to politics what the Beatles were to popular culture. He simply dominated the nation's political landscape, and he personified the new era, not stuffy or hidebound but classless, forward-looking, modern. Even his enemies and detractors, and there were a few, could not deny his brilliance…

Part of Wilson’s brilliance was his quick wit, in evidence throughout the 1960s even if it began to fade in the 1970s. (If you haven’t seen the BBC documentary The Hecklers, based on the people who shout at politicians and our leaders’ response to them, it’s a must-watch and available here). Blair highlighted some of those moments in his tribute:

When a young boy hit him in the eye with a stink bomb at an open-air meeting and was marched off by the police, Harold, whose eye was none the less smarting, looked up and said, "Don't lock him up. With an arm like that he should be bowling for England.”

At the height of the 1964 election campaign, when a lady got up to carry out a crying child, Harold Wilson turned to her and said, "Let him stay, madam. This is all about his future."

He did not always get the best of his tormentors, and one of the good things about him were the stories that he would tell against himself. The best, I believe, was when he was at a vast public meeting. Speaking about the Navy, "I will always defend the Navy," he said, "and why do I say that?" "Because you're in Chatham,” [home of the historic Chatham dockyard,] shouted a voice from the crowd. Knowing that he was beaten, he joined in the laughter and moved on.

At times, Blair’s tribute sounded a little bit like when Boris Johnson speaks about Winston Churchill: intended to flatter himself as well as the object of the praise. Two years before Blair brought Labour back to office in a landslide victory, he praised Wilson for symbolising:

… the new mood of change. There had been 13 years of unbroken Conservative rule… technology and science were revolutionising people's lives, and a cultural transformation in popular arts was waiting to happen. It was an age for… sweeping away the old and ringing in the new, and Harold Wilson captured it.

But he ended on a moving note, quoting perhaps Wilson’s most famous line on the party they both led:

To many, he is defined as a clever politician — and he was. Yet it would be most unfair to let that eclipse his real character and his deep commitment. He had, in the end, a very simple belief in the virtues of social justice and equality and, by and large, throughout his time in politics, he applied them. He once said: "The Labour party is a moral crusade, or it is nothing." That should be his real epitaph and long may it remain so.

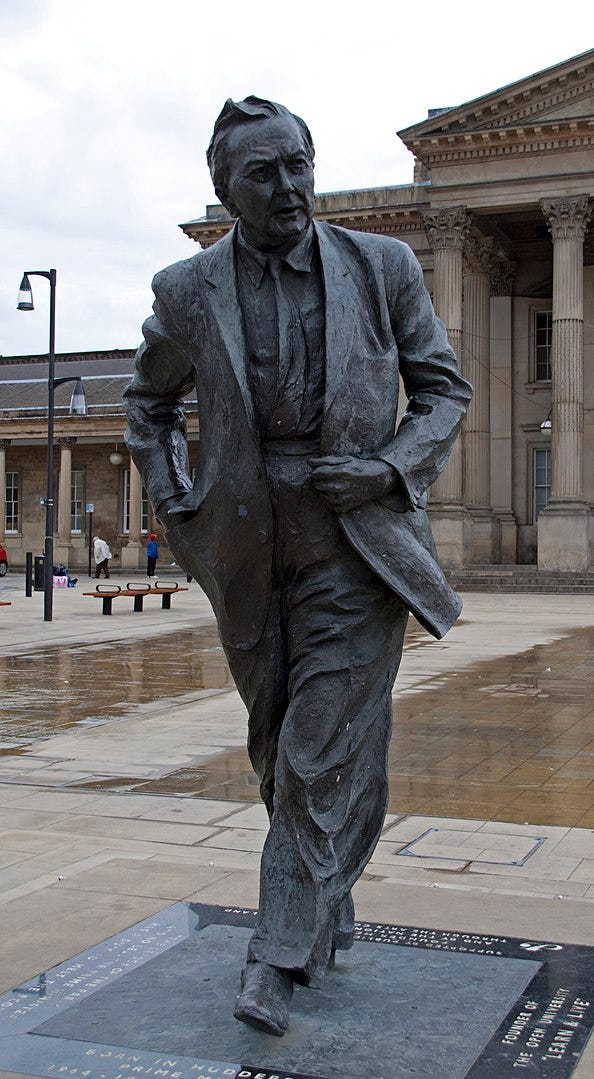

Image: Statue of Wilson in his hometown of Huddersfield by Tony Hisgett

For the Liberal Democrats Paddy Ashdown gave a kind speech, marking the ‘sad day for the House… [and] sad day for our country’ but by this stage it was surely the next speaker, Sir Edward Heath, former Conservative prime minister and now the father of the House, who people wanted to hear from. Heath and Wilson were born in the same year - 1916 - and raised in similar backgrounds. Grammar schools, Oxford and prodigious political talent defined their early lives. They both rose to lead their respective parties and faced each other across the despatch box for a decade (1965-75), fighting four elections against each other.

Sir Edward praised Wilson as a ‘true House of Commons man’ - the words which Wilson, as prime minister, used to describe Churchill upon his death - before adding that Wilson:

… never hesitated to tackle problems and he saw them very clearly. He saw the problem of sterling in the late 1960s. He saw the problem of Rhodesia and tried to resolve it. He not only kept us out of Vietnam, but he saw the problems there and tried to bring peace. He saw the problems of joining the European Community. My greatest regret was that we were never able to come to an agreement about that key policy issue.

When someone dies, memories are often distorted - but, happily, in a cheerier direction than might be the actual truth. And so it was for Sir Edward:

We were together for 35 years—in confrontation, some would say, for more than 10 years as leaders of our respective parties. I would not say that it was confrontation during that time. It was facing each other and arguing about the problems. I like to think that we were constrained. We were not abusing each other and we were not trying to get cheap results quickly from each other.

Heath concluded by assuring Wilson’s widow (who was in the gallery to hear the tributes) that his achievements would be ‘recognised in due course by the country and by the rest of the world’ before adding:

This country owes a great deal to him. We are grateful and we would like Mary and the family to know that today.

The rest of the Commons tributes were similarly generous, often including anecdotes about the Wilson they knew. James Molyneaux, Ulster Unionist MP for Lagan Valley, recalled their time queueing in the café of the House of Commons:

I had ordered a rather exotic dish of scrambled eggs on toast and Harold had picked up a salad from the other cabinet. He said to me, "Jim, would you mind if I bypassed you up to the cash desk?" I took my empty tray from the rails, did a military two steps back, bowed and said, "Prime Minister, I am delighted to yield to an expert in the art of bypassing." Harold was vastly amused at that, took it as a compliment and invited me to share his table when my scrambled eggs eventually arrived.

But Labour’s Edward O’Hara, his successor representing much of the Huyton constituency, was keeping quiet:

I remember much badinage in private in the bar of Huyton Labour club, but I fear that, if I repeated it in the House, it might not pass your rules on parliamentary language, Madam Speaker.

Tony Benn, the former Labour MP for Bristol South East who now represented Chesterfield, had first joined the House of Commons in 1950 when Wilson was President of the Board of Trade. He said (and I have no cause to doubt him) that only he and Heath would have been there to hear Wilson resign from Clement Attlee’s Cabinet over the introduction of NHS charges in 1951. Benn then turned to a recurring theme of the tributes: Wilson’s great skill at party management.

Harold Wilson worked with all wings of the party. Every Prime Minister must think that his Cabinet is difficult, but think of Harold's Cabinet. Two of its members were former members of the Communist party—Lord Healey and Edmund Dell. Two deputy leaders left the party—Roy Jenkins and George Brown. His Minister of Transport, Dick Marsh, joined the Tory party; Christopher Mayhew joined the Liberal party. He stuck it out.

Almost every speech offered a unique angle on the iconic Labour leader. Benn ended by reflecting on Wilson’s political paranoia:

Like all Prime Ministers, Harold Wilson worried about plots. That is not uncommon. I asked him once, when the plot stories were thickening, "Harold, what shall we do if you are knocked down by a bus?" and Harold said, "Find out who was driving the bus."

And Gerald Kaufman, Labour MP for Manchester Gorton, who worked for Wilson for five years in Downing Street, recalled Wilson’s approach to speech-writing:

Unlike many politicians who have followed him, Harold wrote his own speeches. He used to stride up and down the study in No. 10 Downing street, dictating to a succession of secretaries. When the transcript was brought in to him, he would correct it with the green ink that he had always used ever since he was first in the Cabinet. Harold prepared his speeches with meticulous care, and was always extremely careful about the effect that he could create with them.

Image: Wilson’s grave at St Mary's, Isles of Scilly by Bob Embleton

David Harris, Conservative MP for St. Ives, paid tribute on behalf of his constituents on the Isles of Scilly, where the Wilsons had a home, before recalling his pre-Parliamentary experience as a journalist covering the 1964 election campaign:

At the end of the campaign, when the results were coming through, we were in the Adelphi hotel. One can see how times have changed, because the few of us who had followed Harold Wilson around were in his bedroom. He was stretched out on the bed, and I think that he was puffing on his pipe. He turned to me and said, "David, you have followed me all around the country, and you are still a damned Tory!" In that, as in some other things, he was right.

The final person to speak in the Commons was the Speaker, Betty Boothroyd, who singled out her own connection to one of Wilson’s most lasting achievements:

In my view, one of Harold Wilson's lasting achievements was to bring into being the Open university, of which I have the honour to be the current chancellor.

The Commons then adjourned.

Over on the other side of Central Lobby, the House of Lords met the same day to pay its own tribute. Their speeches were fewer in number. Labour’s leader in the Lords, Lord Richard, who had first been elected to the Commons as Wilson became prime minister, echoed a recurring theme from the Commons and reflected on Wilson’s desire to keep the Labour Party united, recalling the time Wilson said:

"This Party is a bit like an old stage coach. If you drive it along at a rapid rate everyone aboard is either so exhilarated or seasick that you do not have a lot of difficulty.” He devoted much time and effort to ensuring that no one fell off.

Lord Richard then read out a message from Wilson’s successor as prime minister, Lord Callaghan, who was in Tokyo when Wilson died. The chamber was robbed of the more fulsome tribute Callaghan would have surely offered in person, but nevertheless he praised Wilson as, ‘the most successful leader that Labour has ever had.’

The next to speak was Lord Jenkins, a Home Secretary and Chancellor in Wilson’s governments, but who now sat as a Liberal Democrat peer having co-founded the SDP and ultimately made his way into the Lib Dems. As one might expect, given Jenkins was one of the best political writers of his or any generation, his was the most literary of contributions - and a suitable place to end:

My Lords, I had a long working relationship with Lord Wilson which at times was very close. It was not without its ups and downs. He and I came from different strands in the sometimes somewhat conflicting fabric of the Labour Party. It was therefore a sign of his tolerance and his generosity that he gave me the great opportunities which led to my working so closely with him. I found, well before his death, that it was the ups rather than the downs which came to dominate my memory…

He was one of the very few Prime Ministers voluntarily to surrender office, to go without the intervention either of debilitating illness or the withdrawal of confidence by Parliament or country. In this century, he and Baldwin stand alone in that respect…

Our sympathy goes out to his family, and in particular to his wife whose devotion in a long twilight has been visible to all of us.

Like this post? Click the ‘heart’ below to help other people find it on Substack. Please also feel free to share this post with anyone you think may be interested.

Wilson at his peak (which, as I’ve written, was I think surprisingly short) had something none of his peers could really match, which was not just wit but lightness of touch. Macmillan had something of the same quality—much more so than Wilson in private—but his, of course, had that stageyness of the Edwardian actor-manager. For a brief time, Wilson seemed ineffable modern and optimistic.