Parliamentary tributes to… Alec Douglas-Home

A few months after Harold Wilson died, the man he removed from Downing Street - Alec Douglas-Home - shuffled off this mortal coil as well. Parliament met to pay tribute to the one year premier.

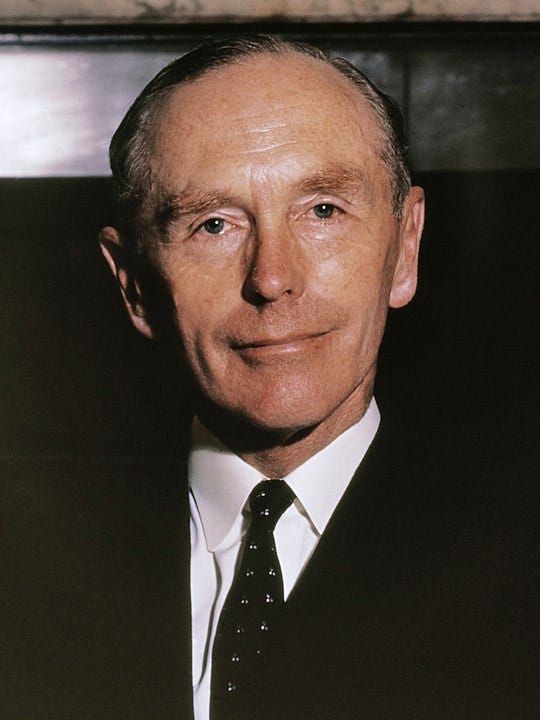

Image: Alec Douglas-Home. Source: Wikipedia.

Parliamentary tributes to… Alec Douglas-Home

by Lee David Evans

Born: 2 July 1903; Died: 9 Oct. 1995

Education: Eton and Christ Church, Oxford.

Parliamentary career: MP for South Lanark, 1931–45; Lanark, 1950–51; and Kinross and Western Perthshire, 1963–1974. Member of the House of Lords as Earl of Home (1951-63); and Lord Home of the Hirsel (1974-1995).

Ministerial career: Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to the Prime Minister, 1937–40; Minister of State at the Scottish Office, 1951–55; Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations, 1955–60; Deputy Leader of the House of Lords, 1956–57; Leader of the House of Lords and Lord President of the Council, 1959–60; Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, 1960–63 and 1970-74; Prime Minister, 1963–64; Leader of the Opposition, 1964–1965.

It’s a miserable thought that even a former prime minister can be so easily forgotten. But that was Alec Douglas-Home’s fate in his own lifetime. On a train journey back to his native Berwickshire in the Scottish borders, Douglas-Home was approached by an elderly couple who professed themselves to be great admirers of the Tory politician. 'My husband and I think it was a great tragedy that you were never Prime Minister', said the lady. ‘As a matter of fact I was, but only for a very short time,’ replied the faultlessly polite Douglas-Home.

Sixty years after he served as prime minister, the forgetfulness of the elderly train hoppers is hardly remarkable. According to YouGov, just 58 percent of Britons have heard of Douglas-Home, making him the least well known prime minister of the post-war period. Whilst consolation can be found in comparison to Baron Grenville, the least well known premier of all who is recalled by just 21 percent of the population (some of whom are almost certainly lying), the forgetting of Douglas-Home is the overlooking of one of the great political figures of the twentieth century.

That, thankfully, is not what the Commons or the Lords did when he died, at the age of 92, in October 1995. In this post, I look at the tributes paid in both houses to this remarkable, if understated, politician.

But before we begin, a note on names and titles. Throughout his life Alec Douglas-Home lived with many different names. He was born Alec Frederick Douglas-Home. In 1918, when his grandfather’s death elevated his father to the peerage, he took on the subsidiary title Lord Dunglass. And so he remained until his own father’s death in 1951, when he entered the House of Lords as the fourteenth Earl of Home. In 1963 he renounced his claim to a seat in the Lords and the corresponding titles for life. He was thenceforth known as Sir Alec Douglas-Home, hanging the bauble of a knighthood, specifically the Order of the Thistle, to his birth name. And that’s how he was known as prime minister and later as foreign secretary until, in 1974, he left the Commons once again and returned to the Lords, not as an Earl but as a baron. From then, until his death in 1995, he was Lord Home of the Hirsel, taking the name of his family home in the Scottish borders. So, the question arises: what to call him? For ease, I refer to him simply as Alec Douglas-Home throughout this piece.

Image: Douglas-Home as a member of the Eton XI in 1921. Source: Wikipedia.

Douglas-Home died on 9th October 1995 at his home in the Scottish Borders. The following week the Commons met to eulogise the former prime minister. John Major, his beleaguered successor-but-four, led the tributes by declaring Douglas-Home ‘one of those people who light up politics with their integrity… a man of many qualities and few pretensions.’

Describing Douglas-Home as a person who never let politics take over his life (although he was involved in politics from the 1920s, when he first stood for Parliament, until his death, as a member of the House of Lords, in 1995) Major injected some humour into his remarks when he said:

During one election, he abandoned the election campaign for a day playing cricket, which I think is a perfectly proper sense of priorities for an Englishman - and a very enlightened sense of priorities for a Scottish man.

The prime minister then touched upon Douglas-Home’s precocious political rise which saw him serve as Parliamentary Private Secretary to Neville Chamberlain as both Chancellor of the Exchequer and Prime Minister. It was whilst supporting Chamberlain in the latter role that Douglas-Home accompanied the premier to Munich to meet Adolf Hitler, a landmark moment in Britain’s attempts to appease the Nazi dictator. Major spoke accurately when he said of Douglas-Home that he was:

… not, of course, personally responsible for the agreements reached, but, with a loyalty that was characteristic of the man, he would never subsequently criticise Chamberlain's actions.

From there, Major’s tribute was principally a catalogue of Douglas-Home’s political posts - Commonwealth Secretary, Foreign Secretary, Prime Minister, and then Foreign Secretary all over again - peppered with anecdotes picked up from those who knew and recalled his long political life. One such tale concerned the day Douglas-Home’s father, the thirteenth Earl of Home, died:

He heard the news in the Chamber. He immediately rushed away, only to discover outside the Chamber that he had forgotten his spectacles. In keeping with the tradition of the House, his return was barred now that he was a part of the other place.

Sir Edward Heath, who would speak later to offer his tribute (see below) added some further colour to Douglas-Home’s transition from commoner to peer - and Heath’s own role in it:

When the news of his father's death came through, it fell to me, as a whip, to rush into the “No” Lobby where I knew that he was voting, grab him by the arm and rush him out, trying at the same time to explain to him quietly and clearly that his father had died and that if he went through the Lobby, having inherited his title, he would be liable to a financial penalty, which I thought thoroughly undesirable. I just managed to get him out in time so he did not commit the grave offence of voting in this House when he had already become a peer.

Although he went to the House of Lords in 1951, Harold Macmillan still appointed him Foreign Secretary just under a decade later. The then prime minister, like so many before and after, came to rely on Douglas-Home - especially his decency and his judgement. Although, as Major recalled, Macmillan didn’t think his foreign minister represented the best of Britain abroad in every respect:

The sight of a British Foreign Secretary climbing from an aeroplane in a rumpled tweed suit amused many foreign dignitaries. As Macmillan later said, "The Foreign Secretary has been accused of many things but never of being the best dressed man in the Cabinet."

Major then wrapped up his remarks, ending with the brilliantly touching words:

Some have said that Alec Home was a politician of another age. The greatest tribute that I can pay him today is simply this: I profoundly hope not.

Tony Blair, who had never met Douglas-Home, was up next to pay tribute on behalf of the Labour Party. He began by praising him as a ‘straight man’ who was ‘genuine, liked and trusted by political foes and friends.’ As an example of how his opponents could grow to like him, Blair recalled the words of Clydeside Labour MP Jimmy Maxton who once said to Douglas-Home in the Tea Room:

Alec, I have been thinking that, come the revolution, I'll have you strung up on a lamp post, but on reflection I'll offer you a cup of tea instead.

Few remember Douglas-Home as a master of political communication (unlike Blair who, regardless of what one thinks of him, excelled in this area above all others). But Blair recognised one of his predecessor’s lines of genius, recalling how he made:

… no attempt to conceal his [aristocratic] background, and by allying it to a self-deprecating sense of humour, Lord Home turned political attacks against those making them… when Harold Wilson mocked him for being the 14th Earl, he remarked that he supposed that Mr. Wilson, when one came to think of it, was the 14th Mr. Wilson.

Blair even found a way of bringing the house out in laughter and needling his opposite number, Major. Recalling how Douglas-Home conducted himself after his narrow defeat in the 1964 election, when he went from prime minister to Leader of the Opposition, Blair said:

… he behaved with his usual dignity. He changed the rules for electing the Tory party leader - a precedent that I understand the present Prime Minister is looking to follow. He supported his successor completely - a precedent that the Prime Minister no doubt wishes was followed. He served under his successor as Foreign Secretary - a precedent that the Prime Minister is perhaps unlikely to follow.

With Blair’s tribute over, next up was David Steel to speak on behalf of the Liberal Democrats. He was not its leader - Paddy Ashdown was - but Steel was a man of the Scottish borders, too, and so he was chosen to speak for his party. He focused on Douglas-Home’s achievements on the world stage, recalling how:

… he pursued Harold Macmillan's wind of change policy towards South Africa. As Foreign Secretary, he could easily have done a deal with Ian Smith in Rhodesia that would have been popular with sections of his party and the press but would have surrendered African majority rights. He steadfastly refused to do that.

The suggestion was that he might have been a tweed-wearing, shotgun shooting aristocratic Tory, somewhat stuck in his old-fashioned ways, but he wasn’t backwards in his views.

Steel went on recalled a time when the pair travelled together from Scotland to London:

One cold winter night, Sir Alec and I were driving together after a dinner in the borders to catch the Edinburgh-London sleeper at Berwick-upon-Tweed where it passed through at about half-past midnight. For those who do not know it, that station consists of one long windswept platform. As we drove along the banks of the Tweed and were about to pass the gates of the Hirsel, he looked at his watch and said, "We will be 20 minutes early at Berwick. Why don't we stop for a drink?"

We drove up the long drive to his stately home and I must admit that I had visions of roaring log fires and butlers with silver trays. Not so. Elizabeth was in London and the place was deserted. We went in by a side door and he blundered about the rambling basement corridor searching for the light switches. He produced a jug of beer and we went upstairs to his high-ceilinged study. The central heating was off and the grate was empty. We sat huddled in our overcoats and he raised his glass in welcome and said, "I suppose you're thinking that we would have been warmer on the station platform."

Image: The Hirsel, Douglas-Home’s home. Source: Wikipedia.

Next up was the Father of the House, former prime minister Sir Edward Heath. Heath’s connection to Douglas-Home went back a long way: the two had served at the Foreign Office together in the 1960s, and when Heath became prime minister in 1970 he invited Douglas-Home to return as Foreign Secretary. Addressing their first innings batting for Britain on the world stage, Heath said:

When Harold Macmillan summoned us and told us that we were both going to the Foreign Office, it was late July. As we left, Sir Alec - or Lord Home, as he then was - said that we should go to his office and that the first thing to do was to settle our priorities. I said, "Of course," and, when we got there, I asked what the priorities were. He said that the first priority was to fix the date of our holidays. I asked what he proposed and he said, "I think you ought to take yours first - you're in more need of them than I." I said, "Thank you very much. I shall go to Venice."

From the foreign office Douglas-Home became prime minister, then Leader of the Opposition, before resigning as Tory chief in 1965. Heath took his place at the helm of the party, but showed regret about the way events had unfolded:

In some ways, I wish he had continued, but it was obvious that he was tired of it all and he firmly resolved that he would not continue because it was better that he should not.

Heath, presumably, wished it had been Douglas-Home who had suffered the shellacking of the 1966 election and that he had come in, fresh faced and unbruised, afterwards, but it wasn’t to be. He concluded by praising Douglas-Home as:

… notable for his modesty, for his genuine nature, for the fact that one could trust him and for the fact that he got his priorities right on every occasion. This country, and Scotland in particular, owes him a great deal.

Tony Benn spoke next. He had played a unique role in Douglas-Home’s life, albeit without intending to. In 1960, when Benn’s father died, he inherited his viscountcy and was evicted from the House of Commons. He spent the next three years fighting for the right to disclaim his peerage and return to the Commons. He was successful in doing so, and the 1963 Peerage Act which enabled him to hand back his title also enabled other peers, including Douglas-Home, to do likewise. That was exactly what Douglas-Home did in October 1963 in order to become prime minister.

Image: Douglas-Home as prime minister. Source: Wikipedia.

Benn acknowledged his role - ‘I was responsible for bringing Lord Home back to be a commoner, which he may not have liked, and to be Prime Minister, which he did like’ - and praised the man he helped, albeit with a caveat:

I cannot think of any major question on which I agreed with him, but his great quality, as has already been said, was that people trusted him - a phrase not often used in political comment nowadays. He was a signpost, not a weathercock.

Benn drew upon his own knowledge of the media and political communications and praised Douglas-Home’s unique style - the sort of approach to politics no spin doctor would ever encourage a prime minister to adopt:

In the media-orientated world in which we live, it is supposed that to succeed people have to have a good image, charisma, sound bites and a spin doctor. But like Clem Attlee before him, Alec Home had an absolute contempt for such gimmicks. He was absolutely content to be himself. I pay my respects to him because he argued his case always with great knowledge, great courtesy, great sincerity, but without ever indulging in abuse. The House might do well to follow that example.

David Trimble, speaking for the Ulster Unionist Party, focused on Douglas-Home’s commitment to the union of nations that is the United Kingdom:

…as a Scotsman Lord Home knew that this diverse United Kingdom is held together by a series of understandings about the relative weights of the parts of the kingdom and about the concern that should exist for the various parts of the kingdom... It is for that sense of balance, which he displayed throughout his life, that he will be most keenly remembered.

Margaret Ewing, for the SNP, took the constitutional point further still to make the case that ‘progress should be made towards the recognition of the aspirations of the Scottish people’ - an issue on which Douglas-Home did not agree with her - before Bill Walker, who represented Tayside North, which covered part of Douglas-Home’s former constituency in Perthshire, shared two bits of wisdom Douglas-Home had offered him:

"There are some very remote parts [of the constituency], some very difficult roads and you will find that in the winter months when you are required to go somewhere for a meeting you will wish that you were not in fact representing that part of Scotland. But when you get there, you will find that the people there make it all worthwhile, and you forget the journey, you forget the difficult roads and you forget all the problems." That was so typical of the man.

The other advice that Sir Alec Douglas-Home gave me, which I have never forgotten, was, "Bill, if you have thought something through carefully and you believe that it is right, stand by it because in time, you will find that you will be shown to be right." I believe that that guide that he had for himself was a guide that all politicians could well follow.

The House of Lords also met to pay its tributes. Such was Douglas-Home’s age that few of the legendary figures of post-war British politics with whom he had served were left. But the icons of the next generation, including Lord Jenkins of Hillhead, praised Douglas-Home, including his contribution to the Lords:

He was a frequent attender in your Lordships' House until fairly recently. I find it peculiarly easy to summon up a picture of that sparse figure and cranial yet benevolent head sitting somewhere between the noble and learned Lord, Lord Hailsham, and the noble Lord, Lord Boyd-Carpenter.

Adopting a literary turn of phrase, as Jenkins could rarely resist, he described Douglas-Home as, ‘the final station of a railway line which may not survive the harsh commercialism of privatisation’ before adding, partly wearing his hat as Chancellor of the University of Oxford:

He was the last, thus far, of Eton's 18 Prime Ministers and the last thus far of Christ Church's 13. But who knows, Fettes and St. John's College are thrusting in the wind. Whatever the future holds, we should cherish the memory of Alec Home, the more so perhaps for we may not, alas, see his like again.

The final word in this tribute piece goes to the Lord Bishop of Norwich who recalled:

My Lords, many years ago I was privileged to spend an evening with Lord and Lady Home at the home of one of my parishioners… even after 25 years the impression upon a young rector remains vivid - a kind of wonder that this man of eminence should be such easy and delightful company. Before my hostess had a chance, he introduced himself as though he expected I would have no idea who he was. That simple and humble courtesy was of course characteristic.

The Bishop then quoted Douglas-Home’s own words on faith - ‘I am glad that I was brought up in the Christian faith and provided with the hope of a God who is a Redeemer’ - before saying, as Douglas-Home, a devoted Christian, would no doubt have appreciated: ‘Well done, thou good and faithful servant.’

Like this post? Click the ‘heart’ below to help other people find it on Substack. Please also feel free to share this post with anyone you think may be interested.

Black and white TV really did Douglas-Home no favours

I believe I’ve mentioned to you before how amused I was by the ‘who exhumed you’ placard held up in protest to him as PM, but now I see a colour picture of the guy it does drive home how much different media options can change the way people are viewed (maybe Marshall McLuhan was right about mediums and message) because he really did look like someone that placard makes sense about in black and white but in colour he looks perfectly normal

The lovely thing about Alec Home is that his good humour and lack of pretension seem to have been wholly authentic, and there are no suggestions to the contrary. He was a man who knew his strengths and his limitations, and knew (though would never say) that those strengths were considerable. And, as I’ve written before, the 1964 general election, unlike, say, 1945 or 1997, was not “unwinnable”. A few nudges to fate and Alec might have held on, which could have had profound effects (Quintin Hailsham thought the Labour Party would not have survived a fourth defeat in its then-recognisable form).