Parliamentary tributes to… Winston Churchill

Earlier this century he was named the greatest Briton, but how did MPs and peers pay tribute to Sir Winston Churchill when he died in January 1965?

Image: Statue of Winston Churchill in Parliament Square, London. Source: Tim Buss.

Parliamentary tributes to… Winston Churchill

by Lee David Evans

In 2002, the BBC asked the British people who was the greatest among them - of all time. After whittling it down to the top ten, advocates were nominated to make the case for each of the heroes - or anti-heroes, in some cases (Oliver Cromwell ranked in tenth place).

The top ten is generally a testament to the sound judgement of the British people. Nelson (argued for by Lucy Moore, the historian) came ninth, Newton (Tristram Hunt, historian and future MP) was in sixth, Shakespeare (Fiona Shaw, actress and director) fifth and Darwin (Andrew Marr, journalist) was fourth. Few would deny any of them their place among the greatest Britons. In a list dominated by men, two women made the top ten: Elizabeth I (who found an advocate in Michael Portillo) in seventh place and Diana, Princess of Wales (Rosie Boycott, journalist and future peer) in third - a status which signals how long the high sentiments which followed her death in 1997 lingered.

Just one place ahead of Diana, in part because of the advocacy of Jeremy Clarkson, was Isambard Kingdom Brunel, titan of the industrial revolution and the man behind the Great Western Railway, Clifton Suspension Bridge and SS Great Britain. But at the top of the list, the pinnacle of all these islands has produced, was Sir Winston Churchill. That a Labour MP, Mo Mowlam, made the case for him demonstrated how much he had become a politician of general renown, not merely a hero of any single party.

Churchill had died less than forty years before the poll, on 24th January 1965. The new Labour government under Harold Wilson was just a few months old. As Parliament gathered to offer its tributes, it was the new prime minister’s job to stand at the bar of the House and read a letter signed by the Queen’s own hand:

I know that it will be the wish of all my people that the loss which we have sustained by the death of the Right Honourable Sir Winston Churchill, K.G., should be met in the most fitting manner and that they should have an opportunity of expressing their sorrow at the loss and their veneration of the memory of that outstanding man who in war and peace served his country unfailingly for more than fifty years and in the hours of our greatest danger was the inspiring leader who strengthened and supported us all.

Confident that I can rely upon the support of my faithful Commons and upon their liberality in making suitable provision for the proper discharge of our debt of gratitude and tribute of national sorrow, I have directed that Sir Winston's body shall lie in state in Westminster Hall and that thereafter the Funeral Service shall be held in the Cathedral Church of St. Paul.

ELIZABETH REGINA.

That task fulfilled, Wilson then moved a motion that the Queen’s message be considered and began his own tribute to ‘a great statesman, a great Parliamentarian, a great leader of this country.’ Wilson spoke in an almost Churchillian tone as he described the reaction to Churchill’s death:

The world today is ringing with tributes to a man who, in those fateful years, bestrode the life of nations… the legend Winston Churchill had become long before his death and which now lives on [is] the possession not of England, or Britain, but of the world, not of our time only but of the ages.

After much recounting of Churchill’s career and wartime service Wilson, who had only entered the Commons at the end of the war but had sat opposite Churchill on the green benches for 19 years, focused on the contribution that Churchill had made to Parliament. He had first been elected for Oldham in 1900 and had represented Manchester North West, Dundee, Epping and Woodford at different periods of his life. His electoral record was not perfect, with rejection by the voters in a 1908 by-election and at the 1922 general election. But so much of his life was spent in the Commons that his return to Parliament in 1924 earned him the title Father of the House in 1959. Of his years as an MP, Wilson said:

But we, Sir, in this House, have a special reason for the tribute for which Her Majesty has asked in her Gracious Message. For today we honour not a world statesman only, but a great Parliamentarian, one of ourselves…

Each of us has [our] own memory [of him], for in the tumultuous diapason of a world's tributes, all of us here at least know the epitaph he would have chosen for himself: ‘He was a good House of Commons man.’

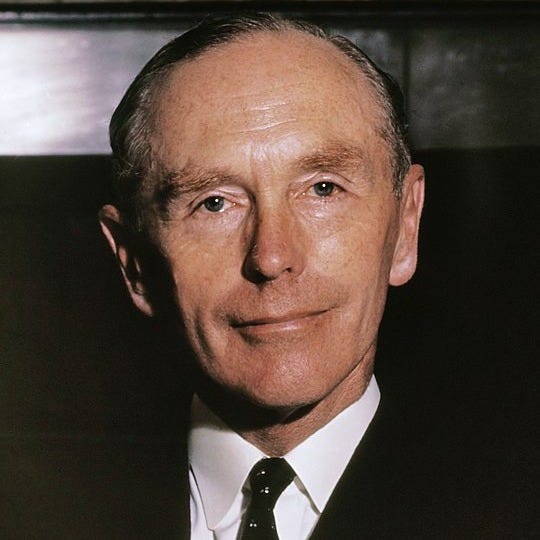

Image: Harold Wilson. Source: Wikipedia

Given that Churchill had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, it was perhaps unsurprising that Wilson injected some literary references into his tribute, highlighting how the great man was steeped in the both British history and literature:

… he drew on all that was greatest in our national heritage. He turned to Byron - ‘blood, tears and sweat.’ The words which he immortalised from Tennyson's ‘Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington’ might well be a nation's epitaph on Sir Winston himself:

Not once or twice in our rough island-story,

The path of duty was the way to glory;

He that walks it, only thirsting

For the right, and learns to deaden

Love of Self, before his journey closes,

He shall find the stubborn thistle bursting

Into glossy purples, which outredden

All voluptuous garden-roses.

The greatest biographer of Abraham Lincoln said in one of his concluding chapters, ‘A tree is best measured when it is down.’ So it will prove of Winston Churchill, and there can be no doubt of the massive, oaken stature that history will accord to him.

Only four MPs spoke in the Commons that day; tributes were not yet the long and almost exhaustive spectacle we have come to know in the years since. Next up was the Leader of the Opposition Sir Alec Douglas-Home. Unlike his predecessor as Conservative leader Harold Macmillan, Douglas-Home had never been especially close to Churchill. (In fact, he had served as PPS to Neville Chamberlain as prime minister before missing two years in Parliament after his diagnosis with tuberculosis in 1940.) Whilst he was appointed as a junior minister in Churchill’s post-war government, it is said that Douglas-Home’s appointment to the Scotland office owed more to his Secretary of State’s mutual closeness to Churchill and Douglas-Home than any enthusiasm on the premier’s part.

Douglas-Home, whom Churchill had apparently nicknamed ‘Home sweet Home’, told the Commons that ‘it did not seem possible that a man could have achieved so much within a mortal span,’ before turning his attention to the:

the rich, full-blooded life which was his… the boyish, infectious zest for living of a man for whom life was an endless adventure; the deep humanity and simplicity, of which the Prime Minister has spoken, of a man with a large heart and an open countenance.

He finished his tribute with a few words to Churchill’s widow, Clementine Churchill, who would soon be granted a place in the House of Lords and would live until 1977:

As we take leave of him, I would like to recall to the House the very last words of the book which he himself called, ‘My Early Life’. In the last few lines, he had been talking of the worries and the struggles of politics and the challenges which he would have to face, and then he wrote this simple line:

‘… until September, 1908, when I married and lived happily ever afterwards.’

To Lady Churchill, who has stood by him all his life and who was with him at the end, we would like to join with the Prime Minister in sending our admiration and our affection, and we stand in homage with the nation.

Image: Sir Alec Douglas-Home. Source: Wikipedia.

All of the party leaders who spoke that day were born and died in the twentieth century. Their task was to pay homage to a man who was first elected to the Commons as a Victorian and served as a prime minister in the second Elizabethan age. In his effort for the Liberals, Jo Grimond sought to highlight the richness of Churchill’s character - warts and all:

From where we stand today it seems as if Sir Winston had been moulded and preserved by fate to lead Britain in her crisis. That was not always the view of his contemporaries. Several times he seemed to have failed. Many people felt that he lacked just those qualities which are said to be essential to the highest office. But it was his supposed defects as much as his acknowledged virtues which entitled him to be called ‘great’.

The sitting was concluded by the backbencher with the longest continuous service, Robert Hugh Turton, MP for the Yorkshire constituency of Thirsk and Malton. He was not yet the father of the house (that title, for a few weeks longer at least, belonged to Rab Butler). But he would soon take on the role and hold it for longer than almost any other MP in the twentieth century (1965-74). On behalf of backbenchers, he spoke of the chamber they sat in and Churchill’s legendary role in its reconstruction after it was bombed in the Second World War:

As this afternoon we sadly leave this Chamber and pass under the Churchill Arch, we will recollect that that arch was left by him untouched and unrepaired to remind Parliament of the fury the Nazis unleashed against this nation and this Parliament. To many of us in future that battered and chipped relic of the former Chamber will be a permanent memorial to the man who loved democratic freedom, who revered our Parliamentary procedure and who in the judgement of all was the greatest Member that Parliament, in all its 700 years, has ever known.

The House closed its sitting by unanimously resolving that a message of reply be sent to the Queen agreeing to the lying in state and the service in St Paul’s.

On the other side of Central Lobby, the same form of tributes took place in the Lords with the Earl of Longford (Labour’s leader of the House) moving the motion as the prime minister did in the Commons. He began with a modest note which often characterised the tone of what at first appears, but in practice rarely is, the grander of the two chambers:

My Lords, only one thing is certain about the tributes that will be paid this afternoon to Sir Winston Churchill: they will be felt, and rightly felt, by their authors to be inadequate to the occasion and to the man.

The peers were conscious that Churchill never sat in their house. He had twice been offered a Dukedom - in what would have been the only non-royal Dukedom of the twentieth century - but declined on both occasions. He appeared to come closest in 1955 when he told Jock Colville that the Queen had made such an offer when he resigned as prime minister:

I very nearly accepted, I was so moved by her beauty and her charm and the kindness with which she made this offer, that for a moment I thought of accepting. But finally I remembered that I must die as I have always been — Winston Churchill.

He omitted, of course, that he would die somewhat more embellished as the Right Honourable Sir Winston Churchill KG OM CH TD DL FRS RA. Despite never joining them, the Lords were fulsome in their praise. Of Churchill’s appointment as prime minister in 1940 and his leadership over the following five years, Longford said:

… gravely, but also gaily, he took our burdens on his shoulders and, to adapt one of his favourite phrases, we all went forward together. It might be asked: How much of the heroic effort that followed was his and how much was ours? Who can say? Who would wish to say? Sir Winston has again and again insisted that all he did was to find a means of liberating and giving full expression to our best and most patriotic impulses, and no doubt, in a sense, that is so. He himself has said: ‘It was the nation who had the lion heart. I had the luck to be called upon to give the roar.’

Viscount Dilhorne speaking for the Conservative benches appealed to Edmund Burke to help in his tribute, recalling the words Burke offered upon the death of William Pitt the Younger:

No man was ever better fitted to be the Minister of a great and powerful nation, or better qualified to carry that power and greatness to their utmost limits.

Lord Rea, the leader of the Liberals in the Lords, appeared almost overwhelmed by the occasion. Fearing he had little to add, his tribute was the shortest of any peer - but no less powerful for it:

I rise with a heavy heart and with abysmal sorrow to try to say the unsayable: to echo inadequately the grief, and also the pride, of thousands of men and women throughout the world who now give heartfelt thanks that our forbears produced such a man as Winston Churchill, that our descendants can look back upon such a mighty figure in our history, and, perhaps a little selfishly, that we of this generation had the honour to live with him. I think there is no more for me to say.

For the Bishops, the Archbishop of Canterbury praised God for giving the world Churchill, and spoke of his commitment to Christendom:

There were two aspects of Christianity that Sir Winston made especially his own. One was the idea of Christendom, a civilisation of charity, justice, and the care for persons — a Christian civilisation. The other was the law of forgiveness, as applied to nations. He could hate and despise a State or a system, but he could feel the bond of humanity with its people and so seek reconciliation after conflict.

Image: Clement Attlee. Source: Wikipedia.

But for this piece, the final word goes to the Earl Attlee, who served alongside Churchill in the wartime government and fought against him in three general elections. (Attlee, despite his own advanced age and frailty, would serve as a pallbearer at Churchill’s funeral). He began by recalling Churchill’s switching of political allegiances with his defection to, and then from, the Liberals:

You might say of Sir Winston that to whatever Party he belonged he did not really change his ideas: he was always Winston.

Attlee then did what people surely wished him to do: spoke of the Churchill he had known so well during the war, of the aspects of his character that others did not see but which Attlee, almost alone among politicians at that time, did. He chose to focus on the compassion Churchill could show:

I do not think everybody always recognised how tender-hearted he was. I can recall him with the tears rolling down his cheeks, talking of the horrible things perpetrated by the Nazis in Germany. I can recall, too, during the war his emotion on seeing a simple little English home wrecked by a bomb. Yes, my Lords, sympathy — and more than that: he went back, and immediately devised the War Damage Act. How characteristic! Sympathy did not stop with emotion; it turned into action.

Before remarking that his old ‘friend’ Churchill was, quite simply, ‘the greatest Englishman of our time — I think the greatest citizen of the world of our time.’

The voters in the BBC’s poll were right.

Like this post? Click the ‘heart’ below to help other people find it on Substack. Please also feel free to share this post with anyone you think may be interested.

Nice piece. That BBC poll managed to come up with a decent top 10, but the ranks of the 100 contained a bizarre number of then current or immediately past footballers and pop stars. Very much dominated by 'recentism'. Worth an analysis by itself?