Ted vs Reggie vs Enoch

Recalling the high drama of the first ever Conservative leadership election between Ted Heath, Reginald Maudling and Enoch Powell.

Ted vs Reggie vs Enoch

by Lee David Evans

The 1964 general election was one of the closest of the century, but the narrowness of the result was irrelevant to the definitiveness with which it ended thirteen years of Conservative rule. The government which had begun in 1951 under the leadership of Winston Churchill had, three old Etonians later (Anthony Eden, Harold Macmillan and Alec Douglas-Home), ended. With Labour’s youthful and grammar school educated leader, Harold Wilson, as the new prime minister, a political, cultural and generational shift had occurred in British politics. The question was: would the Conservatives stick to their old ways under the leadership of Douglas-Home or would they now change, too?

Firing the Starting Gun

Three key events had to happen before a leadership election could take place. The first was to choose a clear mechanism for picking the successor. The incumbent leader Douglas-Home had ‘emerged’, as Conservative leaders traditionally did, via unknown and unknowable processes. His elevation to the top of the party - in which no MP or party member cast a vote - was so controversial that two key members of the Shadow Cabinet, Enoch Powell and Iain Macleod, refused to serve under him in government. It was a blow that Douglas-Home thought cost him the 1964 election and he decided no future leader should be so burdened by the means by which they took the helm of the party. He commissioned a new set of leadership rules in which MPs would vote for who led the party via a series of ballots. (You can read my article on those rules by clicking here). The new rules were adopted in early 1965.

Another matter to be resolved was whether there was going to be an immediate general election. The precarity of Labour’s majority - just four seats - made the prospect of a snap poll ever-present. Yet when Wilson ruled out a 1965 election on 26th June, Conservative MPs were effectively given permission to indulge themselves in a leadership contest.

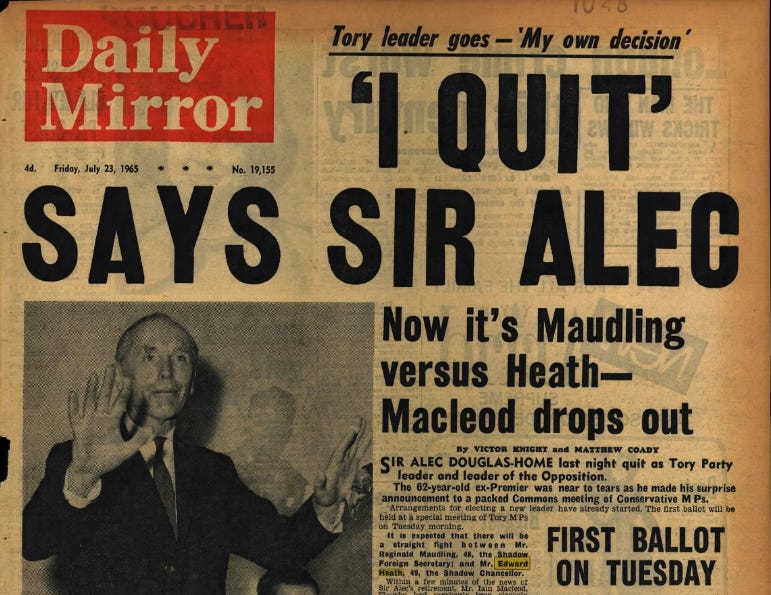

The third and final domino to fall was, of course, the resignation of Douglas-Home. He had planned to continue and no MP publicly declared against him, but there was grumbling among the backbenchers and murmurings in the press. The most consequential critique came from William Rees-Mogg in the Sunday Times, who said it was ‘the right moment to change.’ Douglas-Home took the piece to heart and decided not to stand in the way of a contest if that’s what a significant number of MPs wanted. He met with his Chief Whip and concluded that they did. And so on 22nd July Douglas-Home sent for the Chairman of the 1922 Committee (William Anstruther-Gray), the Party Chairman (Edward du Cann) as well as the two most likely leadership candidates, Edward Heath and Reginald Maudling. He told them he would be resigning. Later, he told the 1922 Committee:

After our narrow defeat in 1964 I knew exactly what I had to do. First to strengthen the organisation of the Party and to eliminate its weaknesses… Secondly, I was determined that the Party should rethink its policies to make certain that they would be up to date and meet the needs of our countrymen… Thirdly, I tried to organise our Party in Parliament so that we would present an effective opposition…

All that being so, I come to two promises which I have always made to you… The first is that I would never allow disunity in the Party, least of all over myself; the second, that I would tell you when I considered that the time was right to hand over the leadership to another. The decision had to be mine and mine alone.

I have to tell you that having weighed to the best of my ability all the considerations I have asked our Chairman, Sir William Anstruther-Gray, to set in motion the new procedures [for electing the leader]. I myself set up the machinery for this change and I myself have chosen the time to use it. It is up to you to see that it is completed swiftly and efficiently, and with dignity and calm. I do not intend to stand for election.

Douglas-Home’s statement fired the starting gun on the first ever Conservative leadership election. In less than a week his successor would be chosen.

The candidates emerge

Reginald Maudling began the contest as favourite. He had been a plausible contender for the leadership in October 1963 (undone, in part, by a poor conference speech) and had served in government as Chancellor of the Exchequer. But from the first days and weeks in opposition, he began to undermine his case for the leadership. After the election defeat, Maudling led the way among senior Tories who went off to earn money with board directorships. He earned thirteen city roles, three of which were full-time. They may have significantly boosted his cash flow, but they also reduced the amount of time he could spend in the Commons earning the affections of his fellow Tory MPs. Edward Heath, on the other hand, took just one, returning to the company at which he had previously been a trainee. His remaining time was devoted to politics.

Another disadvantage for Maudling came in the early 1965 reshuffle. Douglas-Home was keen to make sure all potential and aspiring successors had a platform on which to show off their abilities. He gave the former Chancellor the role of Shadow Foreign Secretary. (Rab Butler, its occupant, had just been appointed Master of Trinity College, Cambridge). This was an opportunity for Maudling to shake off the criticisms that were made of his own Chancellorship in the last government and speak in a new policy area: foreign policy. It could have been a significant boost to his prospects but for two problems. Firstly, foreign policy was Douglas-Home’s own area of expertise and so the capacity provided to the Shadow Foreign Secretary was less than might have been expected. And secondly, it wasn’t in foreign policy where the biggest battle with Labour was going to come. It was the economy.

Into Maudling’s place as Shadow Chancellor went Edward Heath. Heath’s reputation had been on the rise since Douglas-Home requested that he coordinate a review of the party’s policies after the 1964 election defeat. Given Labour’s razor thin majority, the task was urgent; Wilson could go to the country at any time and the Conservatives needed a fresh and compelling offer to the voters. By early 1965 thirty policy review groups had been formed, each chaired by a frontbench spokesperson and staffed by MPs, peers and outside experts. They were tasked with coming up with new policies on issues as diverse as agriculture and immigration, with Heath overseeing the entire process. He was seen as effective and energetic in the role.

Even more important was Heath’s promotion to Shadow Chancellor, which helped seal his status as a plausible leader. The biggest political battles of 1965 concerned the Finance Bill which implemented that year’s Budget. Between April and July, 211 hours of debate over 22 Parliamentary days, including six all night sittings, were devoted to it. Heath was vicious in his attacks and labelled the government’s economic proposals as ‘nasty, brutish and long.’ He went on, ‘It soaks the rich. It also soaks the poor!’ A total of 1,200 amendments were tabled to the Bill. So weak was the government’s position that it was forced to accept 100 Conservative amendments without a division. Heath also managed to coordinate the first government defeats on a Finance Bill in over forty years. Afterwards, he had no doubt that it was this gruelling battle with the government which most aided his chances of becoming leader: ‘above all, I benefited from the way in which we had so thoroughly organised… our attack on the Labour government’s 1965 Finance Bill.’

Heath, however, was not without drawbacks. For one he was a former Chief Whip and many Tory MPs had suffered his sharp tongue in the name of party discipline. Whilst most were pragmatic about the demands of his former job, it gave him a more prickly image than the avuncular Maudling. Heath was also widely associated with Britain’s failed bid to join the European Community under Macmillan, an embarrassment the party has been trying to live down. For other more traditional Tories, too, his modernising habits had been one of the demerits of the last Conservative government. The abolition of Resale Price Maintenance, which created more competition between retailers to the benefit of consumers but was widely seen as harming small business people, was blamed in part for the defeat of 1964. If he was to win the leadership, Heath’s stellar performance in opposition would have to trump his previous flaws in office.

The hours after Douglas-Home’s resignation were dominated by talk of other candidates. It was possible there would be a third or fourth contender. Rumours swirled of candidacies from Selwyn Lloyd, Quintin Hogg or even Iain Macleod, but in the end none of them deigned to put their name forward. Heath and Maudling were joined by just one other candidate: Enoch Powell. Powell referred to his candidacy as a ‘visiting card’ for a possible future bid. For the strategy to work he would need a significant showing on the first ballot, enough to prove that ‘Powellism’ (then much more about free market economics than the racist views he would subsequently be known by) was the view of a serious number of Conservative MPs.

Profiles of the candidates

Edward Heath, 49, Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer

Grammar school boy Heath was educated at Chatham House School, Ramsgate and Balliol College, Oxford. Heath’s Conservative credentials were boosted from a young age: he was a former President of Oxford University Conservatives (1937), Chairman of the Federation of University Conservative Associations (1938), and President of the Oxford Union (1939). During the Second World War, he served in the Army in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany, earning a mention in despatches, an MBE and promotion to Major (1945). He was first elected to serve as MP for Bexley in 1950 and was made a government whip the following year and Chief Whip in 1955, shepherding Tory MPs during the chaos of the Suez crisis. Under Macmillan, he served as Minister of Labour (1959-60) and Lord Privy Seal (1960-3), overseeing the failed negotiations for British entry into the Common Market. Under Douglas-Home he held office as Secretary of State for Industry, Trade & Regional Development and President of the Board of Trade (1963-4).

Reginald Maudling, 48, Shadow Foreign Secretary

Maudling was educated at Merchant Taylors’, a public school, before earning a place at Merton College, Oxford. His political potential took longer to materialise than Heath’s, with Maudling first devoting himself to law and being called to the Bar (Middle Temple) in 1940. He was elected for Barnet in 1950 and first shimmied up the greasy pole when appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Civil Aviation (1952). Later that year he became Economic Secretary to the Treasury (1952-5) before holding office as Minister of Supply (1955-7), Paymaster General (1957-9), President of the Board of Trade (1959-61), Secretary of State for the Colonies (1961-2) and, finally and most consequently, Chancellor of the Exchequer (1962-4).

Enoch Powell, 53, Shadow Transport Spokesman

After being educated at King Edward’s, Birmingham, Powell attended Trinity College, Cambridge and won a series of awards for his scholarship, followed by appointment as a fellow and a Professorship at the University of Sydney (1937-9). He started the Second World War as a Private and made a similarly precocious rise to Brigadier (1944). His Parliamentary career began in 1950 with election for Wolverhampton South West. He was first called for promotion in 1955 to become Parliamentary Secretary for the Minister of Housing and Local Government (1955-7) before earning appointment as Financial Secretary to the Treasury under Macmillan (1957-8), a role from which he resigned in protest over Macmillan’s economic policies. Powell returned in 1960 as Minister for Health, before leaving the government, again in protest, over the appointment of Douglas-Home as prime minister.

The campaign

The party may have transitioned away from ‘emergence’, so often defined by aspiring leaders who didn’t want to be seen doing anything so vulgar as campaigning for the role they desperately courted, but coyness remained a theme of the election. Newspapers asked not whether candidates were fighting for the leadership, but whether they would ‘allow [their] name to go forward for the first ballot.’ ‘None of us carried out a personal public campaign,’ recalled Heath. ‘It was all done by teams of supporters.’ For Maudling, at least, not actively seeking the job provided some psychological comfort:

Had I fought for the leadership as a matter of personal ambition… the weight of subsequent responsibility would have been infinitely multiplied. It would be one thing to be leader of your country because your own supporters wish you to do it. Then you can sleep easy with your conscience if you know you have done your best to fulfil your duty. It would be another thing to sleep easy with your conscience in the dark and dangerous days that inevitably come if you had assumed the responsibility because you had wanted it, fought for it, campaigned for it and contrived for it yourself.

Some may think him daft, but the leader whom duty calls, rather than ambition, is surely the better chief. But who would duty call?

The Heath campaign strategy was to methodically contact every MP to canvas for support, getting the most suitable loyalists to contact the necessary converts and deploying the arguments most likely to win over new support. It meant that the Heath campaign - especially campaign manager Peter Walker - had a remarkable grasp of who was supporting whom throughout the campaign. Maudling’s campaign was a much gentler effort. He surmised that most Tory MPs were knowledgeable and experienced enough to make up their own mind and harassing them to support him would only antagonise them. It was an approach that was consistent with the Tory leadership selections of old. But, with Maudling trying to overcome the worry that he lacked drive for the role, his statesmanlike approach only reinforced the idea that he didn’t want the leadership enough. That is the most generous appraisal, at least. The alternative is that Team Maudling always thought he was going to win and didn't think he needed to bother with the grubby business of winning votes. Powell’s campaign, in the words of his biographer Simon Heffer, was ‘low-profile, and was aimed merely at securing recognition of his and his ideas’ small, but significant, influence in the party.’

Both Heath and Maudling claimed it was a clean campaign. Yet Lewis Baston, Maudling’s biographer, dissents from their rosy view. ‘Conservative Party leadership elections have developed a particularly piquant flavour over the years, of backstabbing and bitchiness of high order. The 1965 leadership election… was no exception.’ For example, at the beginning of the week in which MPs voted, the rumour swirled around Parliament that Maudling was an atheist. Some of his supporters were alarmed and one asked Maudling if he could issue a firm denial. Maudling said, ‘Of course. My wife and I went to Church on Sunday here in Chester Square. It’s funny that nobody bothered to find out and that all the photographers were at the church to which Heath went!’ Maudling supporters suspected foul play.

Just five days after Douglas-Home resigned, MPs prepared to vote. Harry Boyne of the Daily Telegraph wrote, ‘Those who thought of long-term Conservative Government preferred Maudling; those who just wanted to bundle Labour out quickly were all for Heath.’ For those wanting to know what the public thought, an NOP poll published by the Daily Mail suggested that the voters favoured Maudling by 44% to 28% for Heath. (Among Tory voters, the gap was similarly stark: 48% to 31%).

The result

The rules for the contest were anything but simple. In the first round, all MPs would cast one vote by secret ballot for their preferred candidate. If a candidate earned more than half the votes and led the second placed candidate by at least fifteen per cent, they were the winner. If nobody had the required supermajority, the contest began all over again. Earlier nominations were void and new candidates were able to enter the race. To win on the second ballot, a candidate needed just half of MPs to support them. And if nobody met that threshold, a third round would take place between the top three candidates. This time, MPs would express two preferences and their second preferences would be reallocated, if necessary, to determine the winner.

The first ballot was held on Tuesday 27th July. Committee Room 14, so often the scene of Tory leadership drama, was the voting room for MPs, with the ballot open from 11:30am to 1:30pm. Both leading camps thought they would win, whilst Powell - who at one stage had been hoping to attract up to 60 votes - was now expecting a poor finish. After casting his vote, a confident Maudling went for lunch in the city. Heath, meanwhile, spent two hours with his campaign manager, Walker, talking optimistically about the future of the party and the country.

When William Anstruther-Gray, Chairman of the 1922 Committee, announced the results, MPs had voted:

Edward Heath - 150

Reginald Maudling - 133

Enoch Powell - 15

Heath’s campaign team, it turned out, were much more attuned to the mood of the Parliamentary party; Walker’s prediction of 150 votes for Heath, made earlier that day, had proved exact. (He was two out on the other candidates’ totals). Whilst Health had won an absolute majority it was not enough to end the contest as he did not lead Maudling by fifteen percent; as such, there would be a second ballot. However, about an hour after the result, Maudling called Walker to concede the race. ‘The Party had spoken… there was not much point in asking people to say the same thing over again.’ Powell did the same. With neither man putting their name forward for the second round, and no new entrants joining either, Heath was the last man standing. The contest was over. Heath had won.

Analysis

The key question about the first ever Conservative leadership contest is: how did Maudling go from front-runner to also-ran? The biggest factor was the perception that he simply didn’t have the drive for the job. ‘Heath really is a positive force - a leader - while dear Reggie, though very intelligent, does like a good lunch and parties that go on late into the night,’ newspaper proprietor Cecil King reflected. It’s a caricature of the two men that leaves you in no doubt who you would most want to go for a pint with - but also by whom you would most want to be led. Maudling resented the dig: ‘The only thing I resent at all,’ he later wrote, ‘is those people who since that day have occasionally written… that Reggie did not get it because he was too lazy to work hard enough for it. How little do they understand human nature, these fervent scribes!’ But protest as he did, the perception was widespread.

When it came to the voting, Maudling’s supporters claimed that Powell’s derisory fifteen votes would have otherwise been theirs. But when Powell’s candidacy was announced, it was widely expected he would take two votes from Heath for every one from Maudling. Even if this was wrong and their claim to have been second preference for Powell’s supporters is right, it doesn’t matter: Maudling would still have lost, and almost certainly withdrawn. (Powell, for his part, later confided to a friend that he would not have stood at all had he known in advance he would attract just over a dozen votes.)

The final nail in the coffin for Maudling was the weakness of his campaign operation. His team never properly met again after the day Douglas-Home resigned and never appointed a formal campaign manager. Unsurprisingly, their canvassing operation was weak. Philip Goodhart, who campaigned for Maudling, reflected that it was ‘the worst organised leadership campaign in Conservative history: a total shambles.’ As Lewis Baston wrote in his biography of Maudling, ‘The idea of canvassing and recording voting intentions was a new and highly suspect one for some of [Maudling’s] traditionalist supporters. They were not very good at it.’ Later, Maudling met with Walker, who ran a brilliant data-driven campaign for Heath, to exchange notes and found that 45 MPs had pledged to support both candidates. Given the shortfall in Maudling’s expected tally, a large majority of them must have voted for Heath - without the knowledge of the Maudling campaign.

Reports of how people voted must always be taken with a heapful of salt; winners never attract as many votes in ballots as people claim to have cast for them afterwards. Nevertheless, there was a widespread view that Heath attracted the more dynamic and modernising Tories who would play a critical role in the party’s future. Iain Macleod let it be known he was backing Heath, and delivered a majority of the support that would have gone to him, had he stood. Margaret Thatcher backed Heath, too, after being persuaded by Keith Joseph. What made Heath’s campaign ultimately so successful, though, is that he also attracted the higher ranks of the party establishment - inside and outwith the Commons. Former prime minister Harold Macmillan backed him and provided behind-the-scenes support. Rab Butler did likewise. It’s even said that Douglas-Home, whilst coy about how he cast his vote, let it be known that he was backing Heath - even if he wasn’t, the impression that he was added credibility to Heath’s bid for the top job.

In replacing Douglas-Home with Heath, the Conservative Party tried to find its own answer to Harold Wilson. Heath was, at the Daily Mirror said, ‘a new kind of Tory leader - a classless professional politician who had fought his way to the top by guts, ability and political skill.’ Yet as the next decade showed, when Heath battled Wilson in four different elections, Labour had the more effective man. And as we shall see in the next part of this series, once Heath had lost three of the four elections he contested, the party’s patience with him snapped.

Like this post? Click the ‘heart’ below to help other people find it on Substack.

Excellent stuff. There is always the question mark of Maudling's drinking: although it certainly was a factor in shaping his career in the 1970s, whether it was a significant influence in 1965 is hard to say (but, as you note, perception is important and I'm sure it played a part in that). As I said in a recent essay on Wilson, Heath was almost like the Conservative Party had looked at the Labour prime minister and created its own version, but it went horribly wrong. Heath was a terrible leader and an even worse prime minister, though he would never have accepted an iota of criticism. I always think it's a shame (you quite properly touch on it) how many people forget that Alec, the nicest man ever to be prime minister, I think, ran Wilson incredibly close in 1964, and it has been plausibly suggested that if Khrushchev had been ousted a week earlier, Alec's foreign affairs expertise might have swung it the Tories' way. Had that happened, I know Quintin Hailsham thought the Labour Party would have collapsed and a non-socialist centre-left party of some Labour figures, Liberals and left-ish Conservatives would have coalesced.

On Macmillan and Heath:

1. Macmillan had first met Heath when he was an undergraduate at Oxford. Macmillan's son, Maurice, was an undergraduate at Baliol when Heath was President of the JCR. In 1938, Harold Macmillan went to Oxford to support Lindsay, the anti-appeasement candidate, in the "Munich" byelection - both Heath and Maurice were active supporters of Lindsay. Macmillan remained a staunch opponent of the Munichois and there is no doubt that one reason he supported Heath was Heath's record as an opponent of appeasement.

2. Macmillan retained Heath as Chief Whip after he became Prime Minster. On the night of his appointment as PM, he dined with Heath at the Turf Club oysters, game pie, Champagne). Macmillan had told the Queen that he did not expect his government to last six months - in fact it lasted nearly seven years. There is no doubt that Macmillan hugely appreciated Heath's ;loyalty and support especially in the first difficult years and when Salisbury and Thorneycroft resigned.

3. Heath was not just responsible for European negotiations as Lord Privy Seal. The Foreign Secretary, Lord Home, being in the Lords Heath was the senior foreign office minster in the Commons and took Foreign Office questions and (unless Macmillan decided to lead himself) was the main Foreign Office spokesman in debates in the Commons..

4. Heath was an early and firm supporter of Alec Home's candidature for the premiership when Macmillan resigned,. When Alec Home left the Lords and became Prime Minister, Macmillan indicated that in his view Heath, not RAB Butler, would be the better Foreign Secretary. However Alec Home was not in a position to deny Butler the Foreign Office.

5. I have no doubt from conversations with Katie Macmillan, Maurice's wife, who urged Heath to let Alec lose the next election, and also comments by Harold that Heath (unlike Maudling who wanted Alec to stay on) encouraged pressure on Alec Home to step down. In 1975, when another election was held, this time with Heath as Leader, Macmillan was asked (over lunch the Beefsteak what he thought of the Conservative election. His response: "Matthew 26, verse 52" "What is that?:" "He who lives by the sword shall die by the sword."

An additional note: The Chief Whip from October 1964 (appointed by Alec Home) through to 1970 was Willie Whitelaw. Whitelaw was a very close friend of Ted Heath (who of course had been one of his predecessors as Chief Whip) and was promoted under Ted Heath. On must wonder whether Willie saw some advantages in a Ted Heath succession and whether this influenced his reports to Alec Home on the attitude of the Parliamentary Party to Alec staying on.