The rise, fall and surprise return of the ‘stalking horse’

A look at one of the more obscure terms in the Tory lexicon: stalking horse. The latest instalment in the 'Since Attlee & Churchill' series on the history of Conservative leadership elections.

The rise, fall and surprise return of the ‘stalking horse’

by Lee David Evans

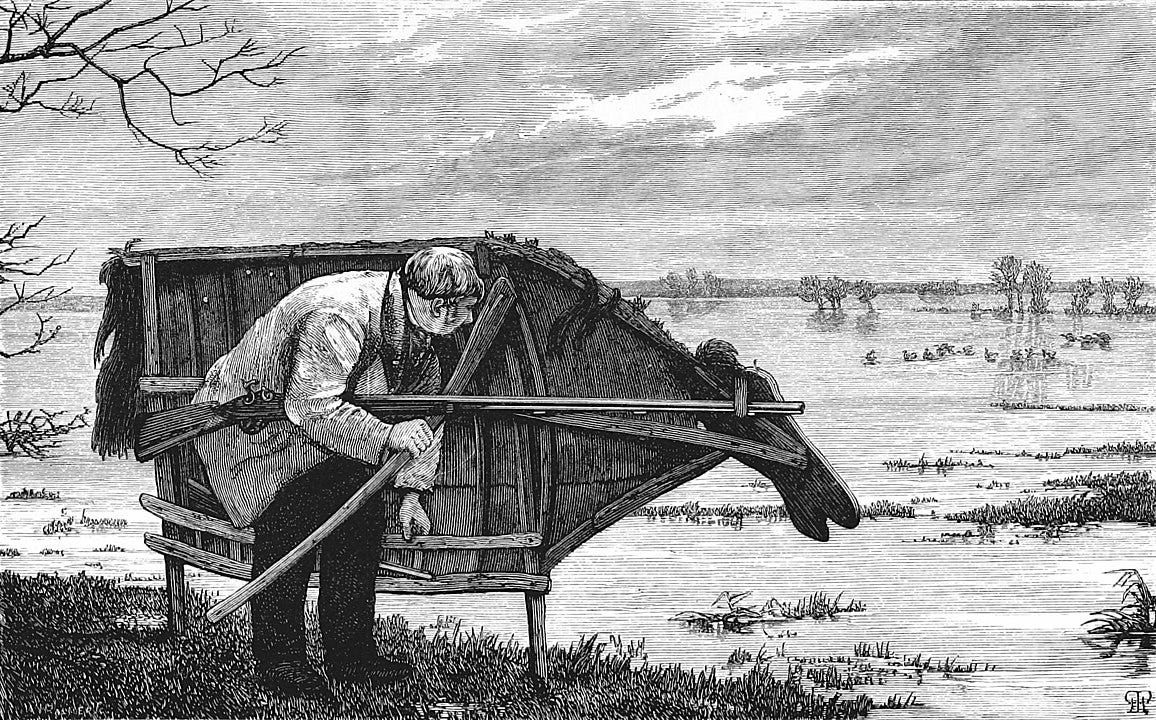

Stalking horse. It’s a term that speaks to a time when backbench Conservative MPs were knights of the true-blue shires. Originally used by hunters to describe techniques of disguising oneself as, with or on a horse in pursuit of game, by the early seventeenth century the stalking horse had been established more generally as a ‘person who participates in a proceeding to disguise its real or more important purpose’. Perhaps it was only a matter of time before a metaphor for deceit and underhandedness made its way from the hunting world to the political.

Stalking horses entered the Tory lexicon after the party’s 1975 leadership reforms. Prior to then, in an arrangement which surely provokes jealousy from recent party chiefs, Conservative leaders had a ‘freehold’ on the top spot in the party. There was no way of removing them. Malcontents wanting to change the leader needed either to persuade them to go or wait for an act of God to intervene. That all changed when Edward Heath, who had led his party to defeat in three of the four elections he contested, felt entitled to lead it into a fifth. Under pressure from his MPs he agreed to a package of leadership reforms which introduced an annual re-election ballot. For the first time Conservative MPs had a means of removing their leader - and used it almost immediately to replace the beleaguered Heath with Margaret Thatcher.

The rise…

Annual leadership ballots, which the party kept up until 1998, may have been expected to generate yearly chaos for the leadership. But the system proved surprisingly stable, in no small part because the ballots were not, as confidence votes are today, up-or-down votes on the leader. Instead, challenges required a challenger. The most plausible alternative leaders were usually in the Cabinet and couldn’t make a bid for the leadership without resigning their position, something they wouldn’t want to do unless they were confident of success. And even when a king or queen across the water was already on the backbenches, a snatch at the crown was often deemed too risky.

Without a publicly declared rival, the incumbent leader would simply be re-elected without a contest. Frustrated MPs, and wannabe leaders reluctant to put themselves forward, needed to find an alternative means of testing the confidence of the parliamentary party in the leader. Enter the stalking horse.

The idea behind the stalking horse was to put up an unlikely candidate for the top job, giving those who favoured a new leader the opportunity to express their lack of confidence in the current one. Whilst there would be no expectation that the stalking horse would win, their candidacy would gauge the mood for change within the party. If enough MPs voted for them, it might persuade the leader to resign, force a second ballot in which more senior colleagues would enter the fray (then possible under Tory rules) or set the scene for a successful leadership challenge the following year. The stalking horse was therefore both a general vehicle for change and a decoy for more serious leadership campaigns waiting for an opportune moment to make their move.