What’s the longest ballot in UK Parliamentary history?

A Canadian campaign group has got me thinking: what's the greatest number of candidates nominated in a Parliamentary constituency?

The latest Since Attlee & Churchill podcast is now available on Apple, Spotify and other podcast platforms. In it, Richard and I discuss Black Wednesday and ask: was it actually a good day for Britain? Click here to listen on Apple, and here for Spotify.

What’s the longest ballot in UK Parliamentary history?

by Lee David Evans

Ballots for the Canadian House of Commons are getting long - very long. Thanks to the Longest Ballot Committee, a campaign group opposed to the use of First Past the Post for Canadian elections, a raft of ‘no hope’ candidates are flooding the ballot in targeted ridings/constituencies.

At Canada’s recent federal election, campaigners targeted Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre’s riding of Carleton, driving the number of candidates up to a staggering 91. Poilievre lost that contest and is now fighting to re-enter the Commons at the Battle River-Crowfoot by-election, a riding recently won by the Conservatives with over 80% of the vote. It looks like a shoo-in, but the Longest Ballot Committee have once again thrown a spanner into the works. 214 candidates have been successfully nominated for the contest, 199 of which have been described as ‘effectively fake.’ The list of candidates is so long that election authorities have decided not to print ballot papers, but are instead asking voters to write the name of their preferred candidate on a piece of paper.

We’ll know in a couple of weeks what the impact of these shenanigans has been on the by-election. But in the meantime, it got me wondering: what’s the longest ballot in a UK Parliamentary election?

Flocking to take on the PM.

The number of candidates standing for Parliament has been rising in recent years. At the beginning of this century, 3,319 candidates stood in the 2001 general election. Last year, the total had soared to 4,515, with nine different parties fielding at least 50 candidates.

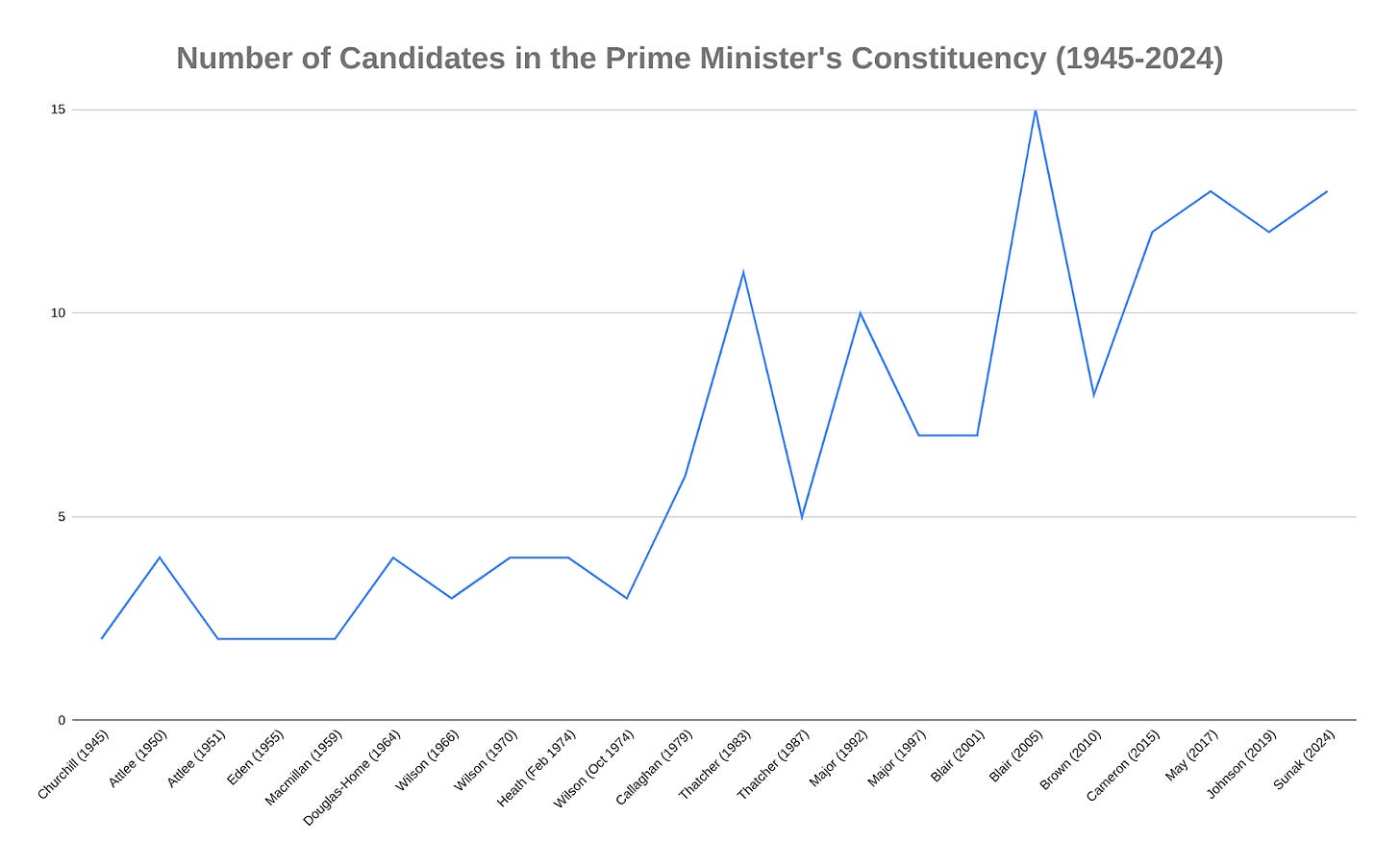

The increase can be seen across the nation, but it has been most marked in the blockbuster constituency contests - which, in a general election, often means the seat of the sitting prime minister. And so to begin the hunt for the longest ballot, I’ve gone back and looked at the number of candidates standing in the constituency of every incumbent prime minister since the war.

Early in the post-war years, prime ministers tended to get away with very few rivals. Churchill, in 1945, had neither a Labour nor a Liberal opponent, and there were never so many as four other candidates on the ballot with a prime minister until 1979.

The number of candidates first hit double-digits in 1983, when ten candidates stood against Margaret Thatcher in Finchley, before a new record was set with 15 candidates in Sedgefield, Tony Blair’s constituency, in 2005. (With Thatcher and Blair winning absolute majorities in their seats, the crowded ballot caused neither leader any concern.) Since 2015, there have been at least ten candidates in every prime ministerial contest - but never again as many as 15.

Seeking the limelight at a by-election.

I’ve searched and searched and I can’t find any general election contest with as many candidates as Sedgefield in 2005. But what about by-elections? These are the other contests that tend to attract a lot of media attention, often enough to persuade people it is worth the effort and cost of getting nominated to stand for Parliament.

Four by-election contests match the Sedgefield record, including the Kensington by-election of July 1988. Candidates in this contest included a self-described ‘Anti Yuppie Revolutionary Crowleyist Vegetarian Visionary’ and a convicted brothel-owner standing for the ‘Rainbow Alliance Payne and Pleasure Party.’ In spite, or perhaps because, of their efforts, the seat remained in Tory hands. The other by-elections with 15 candidates are all pretty recent: Peterborough (2019), Wakefield (2022) and the most recent by-election, Runcorn & Helsby (2025).

Breaking new ground are the four by-elections with 16 candidates. In 1983, the Bermondsey by-election pitted the Liberal Simon Hughes against Labour’s Peter Tatchell, with fourteen other candidates - including a Revolutionary Communist, the National Front, and one candidate just described as a ‘Systems Engineer’ - making up the numbers. The contest is famed for the homophobia which was directed at Tatchell, a celebrated gay rights activist. The safe Labour seat was won by the Liberals.

A similar pattern, sans homophobia, played out in 2003 in Brent East. The constituency had been Labour since it was formed in the 1970s, but the Lib Dems sensed an opportunity when sitting MP Paul Daisley died. Spurred on by the controversy over the War in Iraq, the Lib Dems achieved a 29% swing (the biggest Lab to Lib swing since Bermondsey) to take the seat, seeing off fifteen other candidates.

The other two sixteen-way contests came within weeks of each other in 2021: Hartlepool, arguably the high-point of Boris Johnson’s party leadership; and Batley & Spen, which followed a couple of months later. In the former, the Tories gained a seat from Labour whilst in government. In the latter, Labour’s candidate held on, with Kim Leadbeater fending off both the Conservative candidate and the regular feature of by-election ballots, George Galloway.

Making our way towards the top of the list of the seats with the most candidates, we find two contests with 17 names on the ballot. The first was in 1984 in Chesterfield, when Tony Benn re-entered Parliament after being defeated in his Bristol constituency at the general election the year earlier. Benn was a familiar face in by-election contests: he stood in four - in 1950, 1961, 1963 and 1984 - winning on each occasion, although in 1961 a court ruled his victory invalid.

If Chesterfield saw the return of a famous face, the other seventeen-way by-election was triggered by the departure of an even more famous one. The Uxbridge & South Ruislip by-election in 2023 followed the resignation of Boris Johnson. A whole range of the usual (and not so usual) parties stood, alongside a cluster of independents. At the bottom of the long results table was ‘77 Joseph’, otherwise known as Thomas Darwood, whose given name on the ballot was a reference to Joseph’s interpretation of Pharoah’s dreams in the Book of Genesis. He attracted just 8 votes.

On the bronze podium of lengthy ballot papers is the Kensington & Chelsea by-election of 1999, with eighteen candidates coughing up £500, seventeen of them in an attempt to try and prevent Michael Portillo returning to Parliament. The then safe Tory seat had been held by Tory grandee, diarist and philanderer Alan Clarke. Portillo returned to Parliament without trouble, although he took little pleasure in his second period as an MP and departed the Commons in 2005. Life aboard trains has seemingly proved a happier one than fighting Pro-Euro Conservatives, the UK Pensioners Party, the People’s Net Dream Ticket Party (your guess is as good as mine) and the Earl of Burford to sit on the green benches.

Newbury in Berkshire claims the silver medal, with nineteen candidates on the ballot in the 1993 by-election. This contest marked one of several lows in John Major’s premiership. Judith Chaplin had won the seat with a majority of more than 12,000 in 1992, but when she died the Liberal Democrats hoped to repeat their habit of achieving enormous swings against the Tories, recently seen in by-elections in Eastbourne and Ribble Valley. Alan Sked, the future leader of UKIP, was one of the candidates cluttering the ballot paper (an ageing Enoch Powell spoke for him), but no number of candidates could have prevented a Lib Dem victory. They won almost two-thirds of the vote.

Finally, at the top of the podium, with an absurd 26 candidates, is the Haltemprice & Howden by-election in 2008. That it has seven more candidates than the second placed contest is all the more remarkable as Labour and Liberal Democrats both declined to stand - Labour on the grounds that they thought the contest a farce; the Lib Dems because they said they agreed with the reasons why David Davis, the incumbent MP, had triggered the by-election. Davis was a fierce critic of Labour’s approach to civil liberties, which he deemed authoritarian, and hoped triggering a by-election would spark a debate about the actions of Gordon Brown’s government in passing the Counter Terrorism Act 2008.

More than a dozen independents made the ballot, along with a scattering of minor parties and a few people hoping to promote their cause. There was little in it for most of them. Make Politicians History attracted just 29 votes; Socialist Equality was slightly more popular with 84. Perhaps the surprise performance was the Miss Great Britain Party, which trumped them both with 521 votes and an impressive fifth place finish. Beyond the fringe parties and candidates, Davis was re-elected with just under 72% of the vote. He didn’t really get the debate on civil liberties he so desired, but he did achieve a place, for now at least, in the record books as having triumphed in the face of the longest parliamentary ballot in UK history.

The impact of the deposit.

Whilst 26 is an absurd number of candidates in an election, it’s nothing compared to the 214 fighting it out in Battle River-Crowfoot right now. So why has no British campaign group sought to do the same as the Longest Ballot Committee?

One factor is nominations. On the face of it, the nomination threshold in a Canadian election - 100 signatures - is greater than in the UK, where it is just 10. However, in Canada the same 100 people can nominate as many candidates as are willing. In a UK Parliamentary election, you can only nominate as many candidates as there are vacancies, which is now only ever one. (The same principle applies in local elections, although in these cases the number of vacancies may be higher).

Nevertheless, the relatively small number of signatures required to stand for election in Britain means that you don’t need very many people to get behind you to make it on the ballot. The same 100 people you need in Canada could get ten candidates on the ballot paper. So what else, aside from having not thought of it, has prevented campaign groups bringing about long ballots over here?

The major difference is surely the deposit. To stand for the British House of Commons, you - or your party - need to stump up £500, which will be returned so long as you get more than 5% of the vote. (The deposit itself has an interesting history which I’ll write about one day - including the time I was at an election count and the returning officer agreed, at 4am, to a partial recount to try and get the Lib Dems an extra 0.065% of the vote to save their cash. None of the other parties were happy.)

Canada did have a deposit which, at around $1,000 Canadian dollars is just over £500. But in 2017, a court ruled that the deposit was incompatible with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Longest Ballot Committee was formed two years later. It surely serves as a warning to those of us in the UK to keep a reasonable deposit in place for parliamentary elections, and perhaps even to ensure inflation does not eventually make the cost of standing too trivial, lest our ballot papers become even longer than they have been so far.

Like this post? Click the ‘heart’ below to help other people find it on Substack.

Possibly the closest the UK has come to the Longest Ballot Committee was when the Monster Raving Loony Party put up 13 candidates for a 2021 council by-election in Kingston upon Thames (https://www.andrewteale.me.uk/isqa). Two key differences are that UK local elections have no deposit, and the number of signatures required to stand was reduced from ten to two as a temporary Covid measure (which has since been made permanent).